With the onset of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union (now Russia), the space race became one of the arenas of this conflict. The Soviets held the upper hand in this field, with their technological advancements in space clearly surpassing those of the Americans. Consequently, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was tasked with narrowing this gap by any means possible. To this end, the CIA focused on monitoring and decoding data from Soviet rockets and their satellites while they were still on Earth before launching into space.

The Soviets, showcasing their prowess in space technology, frequently conducted tours to exhibit their achievements to the world. This presented a unique opportunity for American intelligence to attempt to steal one of these Soviet satellites, known as Luna, during one of these tours to study its design and secrets while it was still on the ground.

On January 2, 1959, the Soviet Union launched its Luna space program, sometimes referred to as “Lunik” by Western media. The first spacecraft, Luna 1, missed the Moon, but the second one reached its target, becoming the first spacecraft to land on its surface. In October of the same year, Luna 3 transmitted the first-ever images of the Moon’s far side. This year was remarkable for the Soviets in terms of lunar and space achievements, contrasting sharply with the United States’ few failed lunar missions. This disparity was a blow to American morale, revealing that the Soviets had superior technological capabilities.

In response to this technological gap, the CIA initiated an intelligence program to study Soviet spacecraft and missions. The goal was to better understand Soviet plans and keep pace with their advancements, helping the U.S. military prepare for any potential Soviet threats. This effort involved tracking and intercepting data and communications to gain a comprehensive understanding of Soviet missions. However, due to the challenges of predicting launches and analyzing data remotely, each mission’s information was unique, leading to growing frustration among the program’s personnel. The situation prompted the CIA to undertake a bold operation to unravel the remaining mysteries through a daring plan to steal and examine a Soviet spacecraft, Luna.

The operation relied heavily on Soviet practices between late 1959 and 1960 when they conducted tours in various countries to showcase their industrial and economic achievements, including the Sputnik satellite and the Luna spacecraft. Initially, many CIA agents assumed these were merely display models, but some analysts suspected the Soviets might bring a real spacecraft on these tours. These suspicions were confirmed when CIA operatives managed to access the spacecraft one night after the exhibition closed and realized it was genuine. They gathered some exterior information but needed more details about its internal design.

Due to the heavy security surrounding Luna, examining it before or after the exhibition was challenging. Fortunately, as the components were being prepared for relocation to another city, the CIA devised a complex plan to steal the spacecraft for one night, then transfer it to a train station for its journey to the next city.

When the night arrived, the CIA team executed their plan by arranging for Luna to be the last load to leave the exhibition hall. Once the truck carrying the spacecraft moved, American agents in civilian clothes, disguised as locals, followed to monitor for any expected Soviet guards. Luckily, no guards were present. The truck was stopped at the last turn before the train station, and the driver was escorted to a hotel. The truck was then covered with a cloth and moved to a carefully chosen nearby yard with three-meter-high walls. Meanwhile, other CIA agents monitored the guard at the train station, ensuring he would not return early.

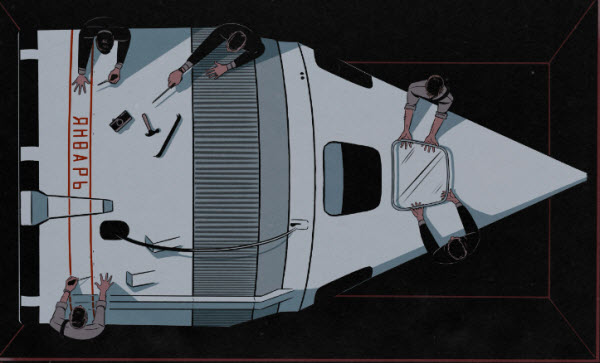

After the guard left, the agents moved the truck into the yard, closed the gate, and waited for thirty minutes to ensure they were not followed. They then inspected the crate, discovering that the sides were secured internally, making the roof the only access point. Two men carefully removed the roof without leaving any marks on the wooden panels. Fortunately, the crate had been opened before, so the wooden panels were slightly worn. The remaining two agents prepared their photographic equipment.

Upon removing the roof, the team found that Luna occupied nearly the entire space of the crate. They hoisted the spacecraft out with ropes and began disassembling and photographing it. They worked throughout the night, and as dawn approached, they reassembled the spacecraft, ensuring no traces of tampering remained, placed it back into the crate, and covered it. By 5 a.m., the original driver returned to the wheel, delivering the crate to the train station. When the guard resumed his shift at 7 a.m., he found the crate as expected and added it to his list. The spacecraft was then sent to the next city with the rest of the exhibits.

The operation was a resounding success. The CIA gained invaluable insights into Soviet space design and technology, significantly narrowing the gap with the Soviets and even surpassing them at one point.