As with many conflicts, the end of World War II saw the victorious Allies scrambling to collect and divide the spoils. Despite their apparent unity, behind the scenes, a fierce competition was underway to acquire the most valuable German assets. These were not natural resources or weapons, but rather a cadre of scientists whose expertise had been pivotal to Germany’s wartime advancements. This treasure trove caught the attention of both the United States and the Soviet Union (now Russia), eager to benefit from their knowledge as the world’s new order began to take shape and the Cold War loomed. In response, the U.S. initiated a covert operation known as Operation Paperclip to bring over 1,600 Nazi scientists to America, offering them immunity and various privileges in exchange for their expertise.

Following the devastating Siege of Leningrad and the significant losses at the Battle of Stalingrad, Nazi Germany failed to defeat the Soviet Union. As the war drew to a close and the Reich’s resources dwindled, Germany urgently needed a new strategy against the Red Army. In 1943, Germany consolidated its most valuable assets—scientists, engineers, technicians, and 4,000 rocket experts—at the Peenemünde Army Research Center on the Baltic Sea in northern Germany. Their task was to develop a technological defense strategy against the Russians. Werner Osnabrück, head of the German Defense Research Association at the University of Hanover, was tasked with selecting scientists for recruitment. He created a detailed list, known as the “Osnabrück List,” stipulating that these scientists should be sympathetic or at least compliant with Nazi ideology.

Meanwhile, the United States became increasingly aware of the Nazis’ secret biological weapons program. Shocked by the program’s sophistication, the Pentagon decided it needed to acquire these weapons for itself. By 1945, as the Allies reclaimed territories across Europe, they also began seizing German intelligence and technology. In March of that year, a Polish lab technician discovered parts of the Osnabrück List hastily stuffed in a university toilet in Bonn and handed them over to American intelligence agents. Initially, the plan was to arrest and interrogate the scientists on the list in a mission called Operation Overcast. However, upon discovering the extent of Nazi technology, the plan swiftly shifted to recruiting these men and their families to continue their research for the U.S. government.

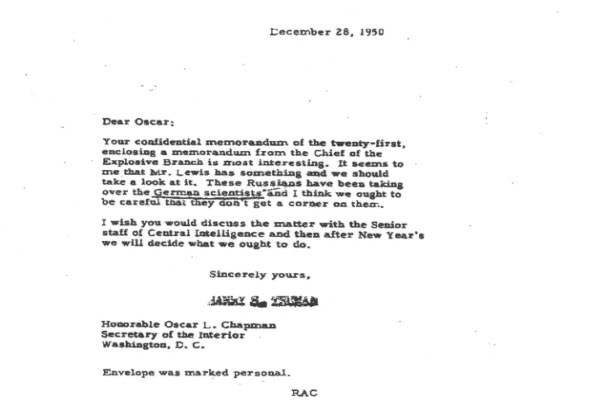

On May 22, 1945, Allied forces invaded Peenemünde and captured the scientists working on the V-2 rocket, the world’s first long-range guided ballistic missile. This became a primary target for the Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA) and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), which would later become the CIA. President Harry Truman greenlit Operation Paperclip, with the stipulation that no committed Nazis should be recruited. However, many of the individuals on the Osnabrück List were Nazi sympathizers, leading the operation to find ways to circumvent this condition by avoiding background checks and erasing incriminating evidence from records.

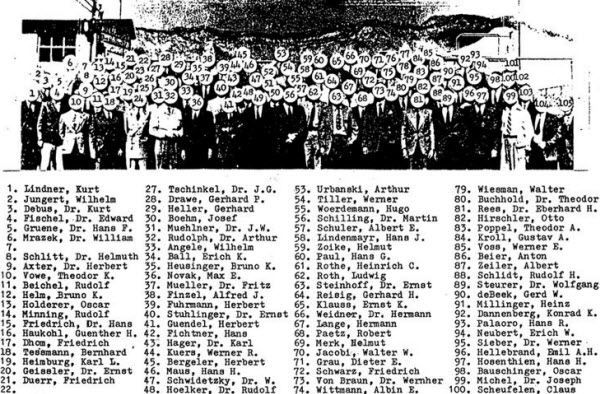

In early August 1945, Colonel Holger Toftoy, head of the U.S. Army’s Rocket Research and Development branch, offered one-year contracts to German rocket scientists, agreeing to sponsor their families as well. 127 scientists accepted the offer. The operation’s name came from U.S. Army Ordnance officers who attached paper clips to the files of these experts. By September, the first group of seven German rocket scientists arrived at Fort Strong in the United States before moving to Texas to test rockets as employees of the War Department. In early 1950, legal American residency was granted to other specialists in Paperclip through the U.S. consulate in Chihuahua, Mexico. They entered the country legally, and 86 German aeronautical engineers were transferred to Wright Field, which acquired Nazi aircraft and equipment. Additionally, the U.S. Signal Corps used 24 German physicists and electronics engineers, and the U.S. Bureau of Mines employed seven scientists in synthetic fuel at the Fischer-Tropsch chemical plant in Louisiana, Missouri. By 1959, 94 more men from Paperclip arrived in the United States, bringing the total number of Nazis who had relocated to 1,600.

Among the most prominent scientists brought over was the leading German rocket scientist Werner von Braun, who had forced prisoners at the Buchenwald concentration camp to work on his rocket program, many of whom perished from exhaustion or starvation. Upon arriving in the U.S. in 1945, he worked on rockets at Fort Bliss, Texas, overseeing numerous V-2 test launches. He continued his research and career progression, eventually joining NASA in 1960. He played a key role in launching the first satellites into orbit on July 20, 1969, as part of America’s effort to win the space race. The U.S. government valued his contributions so highly that it conspired to obscure his past, allowing him to rise to Director of the Marshall Space Flight Center. Despite opposition from a senior advisor, he nearly received the Presidential Medal of Freedom under President Ford, living out his life in peace until his death.

Alongside Braun, almost every major department at the Marshall Space Flight Center was filled with former Nazis, such as Kurt Debus, a former SS member who became the director of what is now the Kennedy Space Center, and Otto Ambros, a chemist favored by Adolf Hitler, who was convicted at Nuremberg for mass murder and slavery but was granted clemency to aid U.S. space exploration efforts and later worked with the Department of Energy.

Much of Operation Paperclip’s history remains shrouded in secrecy. While some journalists attempted to uncover more details in the latter part of the 20th century, their requests for documentation were often denied. However, some requests for declassification were eventually granted, revealing that the American intelligence agency had erased records of the atrocities associated with these individuals. This led to significant controversy between supporters and opponents of the operation, with defenders arguing that the agency sought only to acquire skilled scientists. Yet, new documents have contradicted this claim. Given the Cold War context, it is possible that some American officials believed that showing leniency to Nazi scientists was acceptable in the name of progress and staying competitive with the adversary. Despite being a difficult decision, it was seen as necessary for advancement and keeping pace with the competition.