One of the most controversial figures in history, Joseph Stalin’s reign spanned two decades, during which his policies transformed the Soviet Union from an agrarian society into an industrial power. This transformation elevated the Soviet Union to the status of a global superpower, competing with the United States for dominance during the Cold War era. Stalin’s leadership also halted German advances in Eastern Europe during World War II, eventually pushing them back to their capital, Berlin. However, his rule was marked by severe repression, including executions, arrests, and sending many to labor camps in Siberia, alongside the death of millions due to famines exacerbated by his policies.

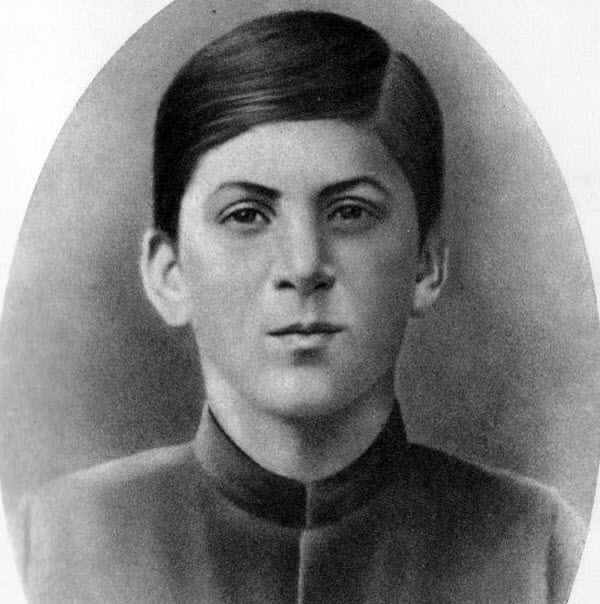

Early Life

Born on December 18, 1879, as Joseph Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili in the village of Gori, Georgia, Joseph Stalin was the son of a shoemaker named Besarion Dzhugashvili and a washerwoman named Ketevan Geladze. As a child, he was frail and contracted smallpox at the age of seven, leaving him with facial scars. A few years later, an accident involving a cart resulted in a slight deformity in his arm. The harsh treatment he received from other children fostered a deep sense of inferiority, driving Stalin to seek greatness and respect.

Stalin’s deeply religious Orthodox Christian mother hoped he would become a priest. In 1888, she managed to enroll him in the Gori church school, where he excelled and received a scholarship to attend the Tiflis Theological Seminary in 1894. During his time there, he became involved with the “Mesame Dasi” organization, a secret society supporting Georgian independence from Russia. Some members of the group were socialist, introducing Stalin to the writings of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin, which profoundly influenced him. He joined the organization in 1898, leaving his studies behind. Various accounts suggest different reasons for his departure, including an inability to pay tuition or his political disagreements with the Tsarist regime of Nicholas II. Regardless of the reason, Stalin did not return to his hometown but stayed in Tiflis, where he worked briefly as a teacher and then as a writer at the Tiflis Observatory. In 1901, he joined the Social Democratic Labour Party and became fully engaged in revolutionary activities.

Participation in the Russian Revolution

In 1902, Stalin was arrested for organizing a labor strike and was exiled to Siberia. During this time, he adopted the name “Stalin,” which means “man of steel” in Russian. Though not a gifted orator like Lenin or an intellectual like Trotsky, Stalin was adept at revolutionary activities such as organizing meetings, distributing propaganda, and coordinating strikes and demonstrations. While in exile, he managed to escape and continued his revolutionary activities clandestinely, including fundraising through robberies, kidnappings, and extortion. His involvement in the 1907 Tiflis bank robbery, which resulted in numerous deaths and the theft of 250,000 rubles (approximately 3.4 million USD), earned him a notorious reputation.

In February 1917, the Russian Revolution began. By March, the Tsar abdicated, and the country was placed under temporary control by a provisional government. The revolutionaries hoped for a smooth transition of power, but in April, Bolshevik leader Lenin opposed the provisional government, advocating for a popular uprising and the seizure of land and factories. By October, the Bolsheviks had seized complete control.

Rise to Power in the Communist Party

The nascent Soviet state experienced significant turmoil as various individuals vied for positions of power. In 1922, Stalin was appointed to a newly created role as General Secretary of the Communist Party. Although initially a relatively insignificant position, it gave Stalin control over all party appointments, allowing him to build a loyal base that consolidated his power. By the time the danger of Stalin’s presence was recognized, it was too late for even Lenin, who was gravely ill, to regain control.

The Great Purge

After Lenin’s death in 1924, Stalin began purging the old party leadership to consolidate his control. Many were exiled to Europe and the Americas, including Lenin’s presumed successor, Leon Trotsky. Stalin’s paranoia led him to instigate a wide-ranging reign of terror, arresting people at night from their homes and subjecting them to show trials. Potential rivals were accused of being capitalist sympathizers and condemned as “enemies of the people,” facing summary executions. No one was spared, whether from the party elite or local officials suspected of anti-revolutionary activities.

Reforms and Their Consequences

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Stalin embarked on a campaign to collectivize agriculture, seizing lands previously granted to peasants and organizing collective farms. He argued that collectivization would boost productivity, but it resulted in widespread peasant discontent and a return to conditions reminiscent of the Tsarist era. Stalin’s brutal response led to the deaths of millions through forced labor and famine. Additionally, his push for industrialization achieved initial success but came at a significant human cost, with millions dying in labor camps. Opponents of his policies faced swift and lethal retribution, while survivors were sent to Gulag labor camps.

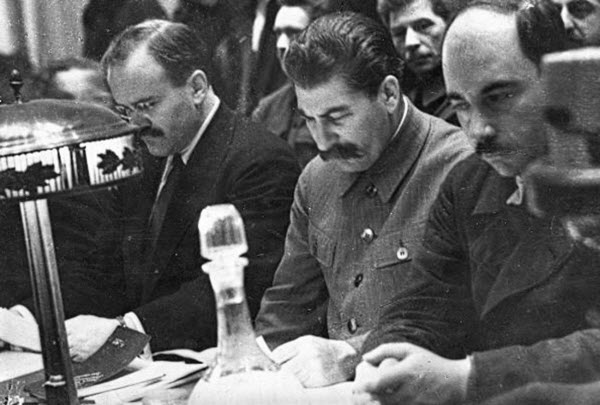

World War II

At the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Stalin made a strategic move by signing a non-aggression pact with Germany, convinced that Hitler would honor the agreement. Ignoring warnings from his military leaders about German troop buildups on the eastern front, Stalin was caught off guard when the Nazis launched a surprise attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941. The Red Army suffered severe losses due to unpreparedness, a consequence of the purges that had weakened the Soviet military and government. Stalin was so shocked by Hitler’s betrayal that he retreated to his office for several days. By the time Stalin regained his composure, German forces had occupied Ukraine, Belarus, and besieged Leningrad. However, Soviet and Russian forces eventually repelled the Germans in the Battle of Stalingrad in 1943.

By the following year, the Soviet army was liberating Eastern European countries even before the Western Allies’ invasion of Normandy. The Soviet forces eventually reached Berlin, leading to Germany’s surrender and Hitler’s suicide.

Relationship with the West

Stalin harbored distrust of the West from the inception of the Soviet Union. He suspected their intentions and, once the war began, demanded that the Allies open a second front against Germany. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt argued that such a move would result in massive casualties for their forces, while millions of Soviet soldiers were dying in battle. As the tide of war slowly turned in favor of the Allies, Roosevelt and Churchill met with Stalin to discuss post-war arrangements. At the Tehran Conference in late 1943, the recent Soviet victory in Stalingrad placed Stalin in a strong negotiating position, leading to an agreement to open a second front against Germany. By February 1945, the leaders convened again at the Yalta Conference, where Stalin agreed to enter the war against Japan after Germany’s defeat. The Potsdam Conference in July 1945 saw a shift in dynamics with Roosevelt’s death in April, replaced by President Harry Truman, and Churchill’s replacement by Clement Attlee. Distrustful of Stalin, the new leaders sought to avoid Soviet intervention in post-war Japan. Fortunately for them, the atomic bombings of August 1945 forced Japan to surrender before the Soviets could intervene.

Foreign Relations

Stalin was obsessed with the constant threat of a Western invasion, which drove him to establish communist regimes in many Eastern European countries between 1945 and 1948, creating a vast buffer zone between Western Europe and the Soviet Union. Western powers viewed this as evidence of Stalin’s intention to impose communist control over Europe, prompting the formation of NATO to counter Soviet influence. In 1948, Stalin imposed an economic blockade on Berlin, hoping to gain complete control, but the Allies responded with a massive airlift, eventually forcing Stalin to retreat. Stalin faced another foreign policy defeat when he encouraged North Korean leader Kim Il-sung to invade South Korea, mistakenly believing the United States would not intervene. Earlier, Stalin’s refusal to recognize the newly established People’s Republic of China led to the Soviet Union’s absence from a crucial Security Council vote supporting South Korea, which passed without Soviet veto.

Number of Deaths

Estimates suggest that Stalin was directly or indirectly responsible for the deaths of up to 20 million people through famines, forced labor camps, and executions. Some scholars argue that his record of murder and terror constitutes a form of genocide, making him one of history’s most brutal figures.

Death

Despite gaining immense popularity from his World War II victories and being portrayed as invincible, Stalin’s health deteriorated in the early 1950s. On March 5, 1953, Joseph Stalin died, leaving behind a legacy of death and fear despite transforming the Soviet Union from a backward country into a major world power.

Even after Stalin’s death and the subsequent revelations of his regime’s atrocities, he continues to find renewed popularity among many young people in Russia today.