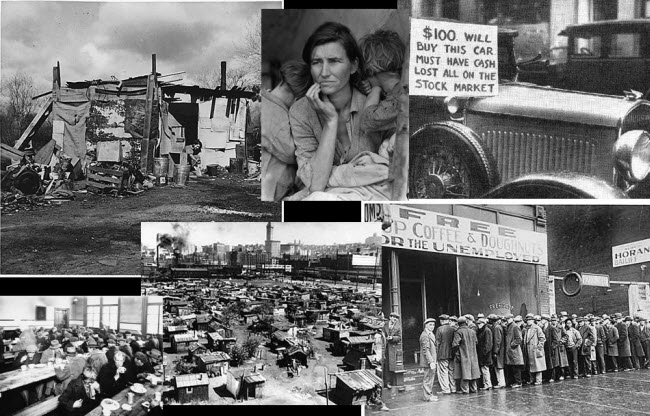

During periods of severe economic downturn, comparisons are often made to the Great Depression, a decade-long economic catastrophe during the 1930s that brought about the most severe economic contraction in modern history. Triggered by a sudden stock market crash in October 1929, this period saw the collapse of Wall Street, wiping out countless investors and causing a dramatic decrease in consumer spending. The resulting surplus of unsold goods led to sharp declines in industrial production, forcing many companies and factories to shut down and lay off millions of workers. Nearly half of the banks in the United States went bankrupt as the crisis deepened.

The Roaring Twenties and the Prelude to Collapse

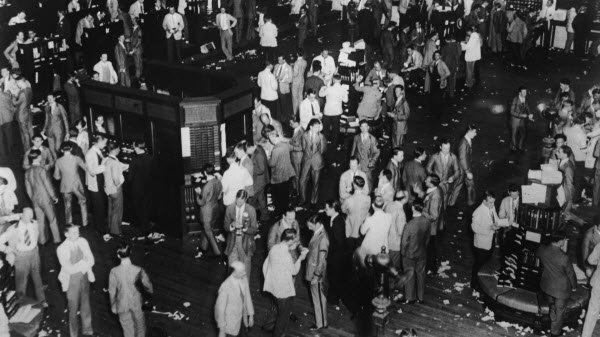

At the start of the 1920s, the American economy was booming, with the nation’s gross national product (GNP) doubling between 1920 and 1929, a period often referred to as the “Roaring Twenties.” This economic boom led many, from millionaires to middle-class citizens, to invest heavily in the stock market. As a result, the New York Stock Exchange in Wall Street experienced rapid growth, reaching its peak in August 1929. This frenzy of stock buying drove prices far above their actual value, while consumer debt soared due to widespread borrowing from banks to purchase stocks. Simultaneously, the agricultural sector was struggling with drought, and banks had made extensive loans that could not be easily liquidated. These factors created a fragile economic environment where consumer goods began to pile up due to slowing sales. Despite these warning signs, stock prices continued to rise, reaching levels that made them highly overvalued by the fall of that year.

The Market Crash

As it became increasingly difficult to make profits from stocks and their values plummeted, panicked investors began to sell off their shares in mass. On October 24, 1929, a day known as “Black Thursday,” the stock market crashed with 12.9 million shares traded in a single day. Five days later, on “Black Tuesday,” October 29, approximately 16 million shares were traded amid another wave of panic, leaving countless stocks worthless and many investors bankrupt. This financial collapse led to a sharp decline in spending and investment, causing factories to slow production and lay off workers. Those who managed to keep their jobs faced significant wage cuts, plunging many Americans into debt. The Great Depression became one of the most severe hardships faced by Americans since the Civil War, and due to the interconnected nature of the global economy, the crisis spread to other nations, particularly in Europe.

The Hoover Administration’s Response

As the economic collapse began, President Herbert Hoover’s administration attempted to downplay its severity, claiming it would be a short-lived downturn. However, the situation deteriorated over the first three years, with unemployment reaching six million by 1931 and industrial production cut in half. Homelessness became widespread across American towns and cities, and many farmers, unable to afford the costs of harvesting, left their crops to rot in the fields while people elsewhere starved. In 1930, severe drought hit the southern plains, bringing strong winds and dust storms from Texas to Nebraska that killed many people and livestock and ruined crops. This disaster forced many rural inhabitants to migrate to cities in search of work, worsening the economic crisis.

Meanwhile, in the fall of 1930, a large number of investors lost confidence in their banks and demanded to withdraw their cash deposits. This forced banks to liquidate loans to shore up their insufficient reserves, leading to the closure of thousands of banks. In response to this dire situation, the Hoover administration tried to support struggling banks and institutions with government loans, hoping that these banks would, in turn, lend to companies that could then rehire employees. However, Hoover, a Republican and former Secretary of Commerce, believed that the government should not directly intervene in the economy or be responsible for creating jobs or providing economic relief to its citizens.

The New Deal Under President Roosevelt

Herbert Hoover’s presidency ended, and Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Democrat, took office in March 1933 amid the deepening Great Depression. By this time, 15 million people were unemployed, accounting for more than 20% of the U.S. population, and thousands of banks had closed, leaving the U.S. Treasury without enough cash to pay all government employees. Despite these daunting circumstances, Roosevelt exuded a calm, optimistic energy, famously declaring, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Roosevelt immediately took steps to address the nation’s economic problems, first announcing a four-day “bank holiday” during which all banks were closed until Congress could pass reform legislation to reopen them on a sound financial basis. He also began addressing the public directly via radio in a series of talks, which went a long way toward restoring public confidence. During his first 100 days in office, Roosevelt’s administration enacted legislation aimed at stabilizing industrial and agricultural production and creating jobs. Additionally, Roosevelt sought to reform the financial system by establishing the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to protect depositor accounts and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to regulate the stock market and prevent the kind of speculative practices that had led to the 1929 crash.

Alongside these economic reforms, Roosevelt’s administration introduced significant social legislation, such as the Social Security Act of 1935, which provided unemployment insurance, disability benefits, and pensions for the elderly. At the time, the United States was the only industrialized nation without some form of unemployment insurance or social security.

The Economic Recovery and Legacy of the Great Depression

Roosevelt’s reforms began to bear fruit, with economic recovery starting in the spring of 1933 and continuing over the next three years as real GDP grew at an annual rate of 9%. Although a sharp recession occurred in 1937, it was quickly overcome within a year.

The hardships of the Great Depression fueled the rise of extreme political movements across various European countries, most notably Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime in Germany, which ultimately led to the outbreak of World War II in Europe in 1939. During this time, the United States began to bolster its military infrastructure while maintaining neutrality. With Roosevelt’s decision to support Britain and France in their struggle against Germany and the other Axis powers, there was an increased focus on building war factories, creating more and more private sector jobs. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 and America’s official entry into World War II, the nation’s factories ramped up to full production. The expansion of industrial production and the military draft that began in 1942 reduced the unemployment rate below pre-Depression levels, bringing an end to the Great Depression and shifting the United States’ attention to the global conflict of World War II.