The end of World War I left the world reeling from unprecedented loss, with approximately 20 million people killed. As the world tried to recover and breathe a sigh of relief, it was hit by another disaster of a different kind: the outbreak of a respiratory pandemic known as the Spanish Flu. This invisible virus wreaked havoc globally, causing an estimated 20 to 50 million deaths—more than double the casualties of the war—and infecting nearly 500 million people, which accounted for about a third of the world’s population at the time. First appearing in 1918 in Europe, the United States, and parts of Asia, the flu spread rapidly across the globe, reaching as far as the Arctic and remote Pacific islands. With no effective drugs or vaccines to combat this deadly strain, governments had little choice but to issue directives for citizens to wear face masks and to close schools, theaters, and businesses until the pandemic finally subsided in early 1920.

What is the Influenza Virus?

The influenza virus, particularly the H1N1 strain, is one of the most well-known respiratory viruses, notorious for its high contagion rate. When an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks, droplets containing the virus can be expelled into the air and inhaled by anyone nearby. Infection can also occur through contact with contaminated surfaces followed by touching the mouth, eyes, or nose. The flu is a seasonal virus that typically spreads each year from late fall to spring. Its severity can vary depending on the mutation of the virus. Annually, flu complications result in the hospitalization of at least 200,000 Americans, and over the past three decades, flu-related deaths have ranged from 3,000 to 49,000 per year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Symptoms and Severity

The symptoms of the influenza virus can sometimes be mild, including chills, fever, and fatigue, with most patients recovering within a few days. However, more severe strains can lead to serious complications such as pneumonia, ear and sinus infections, and bronchitis, which can cause death within days or even hours of symptom onset. In such cases, the skin of those who succumbed often turned blue, and their lungs filled with fluid, leading to suffocation. Although the flu is typically a seasonal virus, it can sometimes become highly contagious and spread epidemically, as seen in 1918 when a new and virulent strain of influenza emerged. This strain, for which there was little to no immunity, contributed to a significant drop in the average life expectancy in the United States by twelve years.

The flu virus particularly affects young children, people over the age of 65, pregnant women, and individuals with certain medical conditions such as asthma, diabetes, or heart disease.

The Spread of the Spanish Flu Pandemic

The Spanish Flu pandemic occurred in three waves. The first wave appeared in early March 1918, during World War I, and although its origins are unclear, the virus spread rapidly across Western Europe. By July, it had reached Poland. This initial wave of influenza was relatively mild, with death rates similar to the annual flu. However, during the summer, a more virulent and highly contagious strain was identified, sparking the second wave in the latter half of August. This wave was often characterized by rapid onset pneumonia, with death typically occurring within two days of the first symptoms. For example, at Camp Devens in Massachusetts, within six days of reporting the first case, there were over 6,500 new cases. October of that year was particularly deadly, recording the highest death toll throughout the pandemic. By December, the second wave had ended, but a third wave soon began in January 1919. This wave was less deadly than the second but more severe than the first. During the second and third waves, about half of the deaths occurred in individuals aged 20 to 40 years, an unusual age pattern for influenza fatalities.

Origin and Naming of the Spanish Flu

The exact origin of the deadly influenza strain that caused the 1918 pandemic is unknown. However, it was first observed in 1918 in Europe, the United States, and parts of Asia before spreading within months to every corner of the globe. Some theories suggest it began at a British army base in France, while another, though disputed, suggests it started in northern China and was brought to Europe by Chinese laborers. Another notable theory proposes that it originated at Camp Funston in Fort Riley, Kansas, USA, in March 1918, with the first case being a camp cook named Albert Gitchell. Despite the fact that the pandemic was not localized to one region, it became known worldwide as the “Spanish Flu” because Spain, which was neutral during the war, was heavily affected by the disease. Unlike other European countries, Spain’s press was not subject to wartime censorship and extensively covered the pandemic, leading many to mistakenly believe that the flu originated there. In reality, neighboring countries had imposed strict censorship to maintain morale at the front lines, leading Spanish health officials to be unaware that other countries were also affected. Some even believed it had originated in France and called it the “French flu,” while the French initially called it the “American flu” before switching to “Spanish flu” to avoid offending their American allies. In Africa, it was referred to as the “white man’s disease,” and the Poles called it the “Bolshevik disease.”

An unusual aspect of the 1918 flu was its high infection and death rates among young, healthy adults, who typically possess strong immunity against such illnesses. In stark contrast, more American soldiers died from the flu than in battle during the war. About 40% of the U.S. Navy and 36% of the U.S. Army contracted the flu, and the movement of troops around the world in crowded ships and trains facilitated its spread. It is believed that India suffered greatly, with at least 12.5 million deaths. The disease even reached remote islands in the South Pacific, including New Zealand and Samoa. In the United States, approximately 550,000 people died, with most deaths occurring during the second and third waves.

Although the number of deaths attributed to the Spanish Flu is often estimated at around 20 to 50 million worldwide, some estimates suggest up to 100 million victims, about 3% of the global population. It is impossible to know the exact numbers due to the lack of medical record-keeping in many places at the time. However, it is known that few areas were immune to the pandemic, such as remote communities in Alaska. It is also reported that U.S. President Woodrow Wilson contracted the flu in early 1919 while negotiating the Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I.

Combatting the Spanish Flu

When the pandemic struck, doctors and scientists were unsure of its cause or how to treat it. Unlike today, there were no effective vaccines or antiviral drugs to treat the flu; the first licensed flu vaccine appeared later in the United States in the 1940s. By the next decade, manufacturers could routinely produce vaccines to help control future outbreaks. During the pandemic, however, the situation was complicated by the fact that World War I had left parts of the United States short of doctors and other health workers, many of whom contracted the virus themselves. In some areas, hospitals were so overwhelmed with influenza patients that schools, private homes, and other buildings had to be converted into makeshift hospitals, some staffed only by medical students.

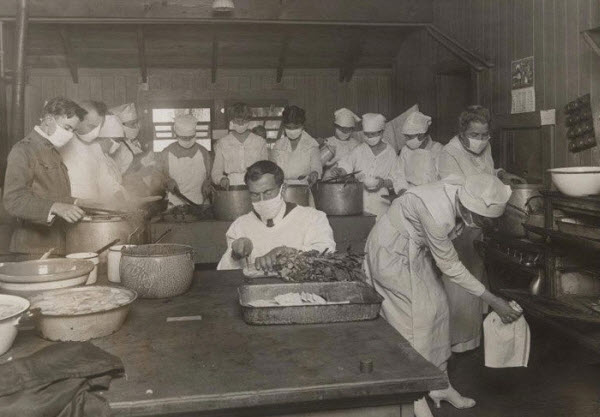

Due to the rapid spread of the virus, officials in some countries imposed quarantines and mandated mask-wearing. They also closed public places, including schools, churches, and theaters, and issued guidelines advising people to avoid handshakes, maintain social distancing, and stay home. Libraries stopped lending books, and regulations were enacted prohibiting spitting. According to The New York Times, during the pandemic, Boy Scouts in New York City would approach people they saw spitting on the street and hand them cards that read, “You are violating the health law.” Fines were imposed on those who did not wear masks, with charges of disturbing the peace.

With no cure for the flu, many doctors prescribed medications they believed might alleviate symptoms, including aspirin, which was patented in 1899, and its patent expired in 1917, allowing new companies to produce it during the pandemic. The Journal of the American Medical Association recommended its use, and specialists advised patients to take up to 30 grams per day, a dosage now known to be toxic since current medical consensus is that doses over four grams are unsafe. Symptoms of aspirin poisoning included hyperventilation and pulmonary edema, or fluid accumulation in the lungs, and it is now believed that many of the increases in death rates in October were due to aspirin poisoning.

The Aftermath of the Pandemic

The Spanish Flu caused massive human losses, wiping out entire families and leaving countless widows and orphans. Funeral parlors were overwhelmed, and bodies piled up, forcing many to dig graves for their family members themselves. The pandemic also took a toll on the economy in the United States, where businesses were forced to close because so many employees were ill, and essential services like mail delivery and garbage collection were disrupted due to sick workers. In some places, there were not enough farmworkers to harvest crops. State and local health departments shut down, hindering efforts to document the pandemic’s spread in 1918 and provide the public with answers about it.

The End of the Spanish Flu

By the summer of 1919, the Spanish Flu pandemic had ended, although the reasons for its conclusion remain unclear. Some theories suggest that the end of the war played a significant role in reducing the spread of infection, increased availability of drugs, developments in immunity among those who survived, a mutation of the virus making it less severe, or a combination of all these factors. Nearly 90 years later, in 2008, researchers announced that they had discovered the reason why the Spanish flu was so deadly. Scientists at the National Institute of Health (NIH) studied preserved samples of lung tissue from victims of the 1918 flu and concluded that the victims had died because their lungs were damaged when their immune systems overreacted to the virus. The effect was particularly strong among healthy young adults with robust immune systems, which explained why so many died during the pandemic.

In addition, the pandemic spurred research into preventive vaccines and flu treatments, which helped pave the way for increased global understanding and preparedness for future pandemics. In 1919, the year after the pandemic subsided, the International Bureau of Public Health was founded in Vienna to coordinate international responses to pandemics. The organization’s role was to monitor global public health and alert member countries to potential outbreaks. This was the first major international effort to prevent and respond to pandemics. A century later, in 2018, researchers announced the discovery of new flu strains that had remained hidden for decades in the samples of lung tissue from Spanish flu victims, revealing that the virus had evolved into a more virulent strain than previously thought.

The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918–1919, unlike other pandemics, did not lead to significant medical or public health advances. Unlike the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020, it did not prompt the widespread use of vaccines, the development of new antiviral drugs, or the establishment of international health organizations. It did, however, bring into sharp focus the devastating impact that a pandemic could have on global health and underscored the need for coordinated international efforts to prevent and respond to future outbreaks. As one of the deadliest pandemics in history, it left an indelible mark on global health, public health policy, and the scientific community, providing valuable lessons that have shaped our approach to managing infectious diseases today.