The Red Cross is an international humanitarian organization established in Switzerland in 1863, encompassing nearly 97 million volunteers, members, and staff across branches worldwide. Its crucial services include aid for disaster victims, armed conflict survivors, and health crises. The organization’s origins trace back to 1859 when Swiss businessman Henry Dunant witnessed the massive bloodshed following the Battle of Solferino in Italy. The lack of medical support for wounded soldiers inspired him to advocate for a national relief organization composed of trained volunteers who could assist all war casualties, regardless of their side in the conflict. This idea received widespread support from many nations. Over the years, the Red Cross’s humanitarian activities have granted it significant international influence and numerous awards, including multiple Nobel Peace Prizes.

The History of the Red Cross

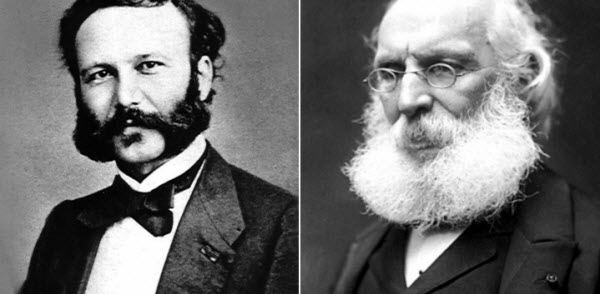

In 1859, Swiss businessman Henry Dunant traveled to northern Italy to meet with French Emperor Napoleon III to discuss business. During his journey, he encountered the aftermath of a bloody battle near the small village of Solferino, where French and Sardinian forces clashed with Austrian troops. The conflict resulted in 40,000 casualties, including dead, wounded, and missing soldiers. Dunant observed that both armies and local civilians were ill-equipped to handle the crisis. He stayed for several days, dedicating himself to helping and caring for the injured. By 1862, he published a book titled A Memory of Solferino, recounting his experiences and calling for the creation of national relief organizations with trained volunteers to assist wounded soldiers regardless of their combat side. The following year, a committee was established in Switzerland, which Dunant was part of, to create a plan for national relief societies to aid the wounded. This committee later became known as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

The committee issued several key recommendations, including the establishment of national relief societies for soldiers, strict neutrality, and that individuals providing battlefield assistance be volunteers. They also proposed organizing additional conferences to formalize these concepts and introduced a distinctive protection symbol, the red cross on a white background, which was the inverse of the Swiss flag. By late 1863, the first national society was founded in Württemberg, Germany. A year later, 12 countries signed the original Geneva Convention, advocating humane treatment of sick and wounded soldiers regardless of nationality, and proper treatment of civilians providing aid. In 1867, Dunant faced financial setbacks leading to bankruptcy and had to resign from the Red Cross. However, by the 1870s, many countries embraced this idea, with the Ottoman Empire adopting the Red Crescent instead of the Red Cross due to its experience in the Crimean War (1853-1856), where diseases overwhelmed the battlefield, leading to high Turkish soldier casualties. The Red Crescent became the first such organization, followed by other Islamic countries. In 1901, Dunant was awarded the first Nobel Peace Prize, recognizing that without his efforts to establish the Red Cross, such a significant humanitarian achievement in the 19th century might not have been possible.

World War I

With the outbreak of World War I, the International Committee of the Red Cross faced unprecedented challenges, which it could only address by closely collaborating with national Red Cross societies. Nurses from around the world, including from the United States and Japan, came to support the medical services of European countries involved in the conflict. The organization established the International Prisoner of War Agency (IPWA) to track prisoners of war and act as an intermediary between them and their families.

During the war, the committee monitored compliance with the Geneva Conventions by warring parties and addressed complaints of violations, especially as chemical weapons were used for the first time in history. The ICRC strongly protested their use and sought to alleviate civilian suffering in officially recognized occupied territories. It conducted inspections of prisoner-of-war camps, with 41 Red Cross delegates visiting 524 camps across Europe.

By the end of the war, the agency had transmitted approximately 20 million messages, 1.9 million parcels, and about 18 million Swiss francs in cash donations to war prisoners from all affected countries. It also facilitated the exchange of around 200,000 prisoners between warring parties and their repatriation. For these efforts, the Red Cross was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1917, a year before the war officially ended.

World War II

The Geneva Conventions’ 1929 revisions provided the legal foundation for the ICRC’s work during World War II. The Red Cross’s activities during this conflict mirrored those of World War I, including monitoring and visiting prisoner-of-war camps, organizing relief for civilians, and managing correspondence for prisoners and the missing. By the end of the war, 179 delegates had conducted 12,750 visits to prisoner-of-war camps across 41 countries, and the agency exchanged 120 million messages. However, significant challenges arose, including the refusal of the Nazi-controlled German Red Cross to cooperate with the Geneva Conventions or address gross violations like mass killings in Nazi concentration camps. Additionally, the Soviet Union and Japan, not signatories of the Geneva Conventions, were not bound by its rules.

During the war, the ICRC was unable to secure agreements with Nazi Germany on the treatment of detainees in concentration camps and eventually ceased its pressure to avoid disrupting its work with prisoners of war. It also failed to obtain responses about verified information on extermination camps and mass killings of European Jews, Romani people, and others. Nevertheless, the International Red Cross was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize again in 1944, recognizing its continued efforts during the war.

Post-World War II

To celebrate its centennial in 1963, the ICRC, in collaboration with the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, received its third Nobel Peace Prize. Since 1993, non-Swiss individuals have been permitted to serve as ICRC delegates abroad, a role previously restricted to Swiss citizens. This change increased the proportion of non-Swiss staff to about 35%.

In October 1990, the United Nations General Assembly granted the ICRC observer status at its sessions and subcommittee meetings, making it the first private organization to achieve this position, a decision proposed jointly by 138 member states. In March 1993, the ICRC signed an agreement with the Swiss government to reaffirm its long-standing policy of complete independence from potential interference. This agreement protects all ICRC property in Switzerland, including its headquarters and archives, grants legal immunity to its members and staff, exempts the ICRC from all taxes and fees, and ensures duty-free transportation of goods, services, and funds. It also provides the ICRC with secure communication privileges equivalent to those of foreign embassies and facilitates the travel of its members within and outside Switzerland.

Following the end of the Cold War, the ICRC’s work became more perilous. During the 1990s, several delegates lost their lives more than at any other time in its history, particularly in local armed conflict zones, highlighting frequent disrespect for Geneva Convention rules and protection symbols.

The Organizational Structure of the Red Cross

The ICRC’s headquarters is located in Geneva, Switzerland, with external offices in approximately 80 countries. It employs 12,000 staff worldwide, including 800 at the headquarters, and 1,200 expatriates, half of whom work as delegates managing international missions, while the other half are specialists like doctors, agricultural engineers, engineers, and interpreters. Around 10,000 are members of individual national societies. Under Swiss law, the ICRC is defined as a private association. Contrary to popular belief, it is neither a non-governmental organization (NGO) nor an international organization since its membership is restricted to Swiss citizens only, thus not following the open and unrestricted membership policies of other legally defined NGOs. The term “international” in its name refers to the global scope of its activities as defined by the Geneva Conventions, rather than its membership. The ICRC enjoys special privileges and legal immunities in many countries.

According to its statutes, the Red Cross is composed of two main bodies: the General Management, consisting of a Director-General and five managers in the fields of Operations, Human Resources, Resources and Operations Support, Communications, and International Law and Cooperation within the Movement. They are appointed for four-year terms by the other body, the Assembly and its Council (a sub-body with delegated powers). The Assembly, with 25 Swiss members elected by their peers, is chaired by the same person who heads the Council. The Council, consisting of all Assembly members, meets regularly and is responsible for setting goals, guidelines, and strategies, overseeing financial affairs, and electing a five-member decision-making board for some matters. This board also organizes Assembly meetings and facilitates communication between the Assembly and General Management.

In 2009, the ICRC’s budget exceeded one billion Swiss francs, with most funds coming from states, including Switzerland, national Red Cross societies, signatory states to the Geneva Conventions, and international organizations like the European Union. All payments to the ICRC are voluntary and are received as donations based on two types of appeals: an annual appeal for headquarters costs and emergency appeals for individual missions.

The Red Cross and the United States

Following the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, Clara Barton, a former teacher who worked at the U.S. Patent Office in Washington, D.C., began volunteering to deliver food and supplies to Union soldiers on the front lines, earning her the title “Angel of the Battlefield.” By the end of the war, she received authorization from President Abraham Lincoln to manage the Office of Missing Soldiers, tasked with helping locate missing individuals from the army and determining their fates for their families and friends. Over several years, Barton and her staff received more than 63,000 letters requesting assistance and managed to trace around 22,000 men. In the late 1860s, Barton traveled to Europe to recover and rest from her years of hard work during the war, where she learned about the Red Cross movement.

Upon returning to the United States, Clara Barton launched a years-long campaign to encourage her country to ratify the 1864 Geneva Convention, achieving this goal in 1882, a year after founding the American Red Cross. Under her leadership, the organization focused on assisting disaster victims during peacetime, such as the Johnstown flood in Pennsylvania in 1889, which claimed over 2,000 lives, and the 1893 hurricane in the Sea Islands of South Carolina, leaving around 30,000 people homeless, mostly African Americans. During wartime, the American Red Cross collaborated with the military in 1898 to provide medical care to soldiers during the Spanish-American War. In 1904, Barton resigned as President of the American Red Cross at the age of 83.

In the early 20th century, the American Red Cross expanded its efforts to include public programs such as first aid training and water safety. During World War I, the organization experienced significant growth, expanding from 100 local branches in 1914 to over 3,800 branches in four years. The American Red Cross recruited 20,000 nurses for military service and supported American and Allied forces as well as civilian refugees. During World War II, the organization recruited over 104,000 nurses for the armed forces and sent over 300,000 tons of supplies abroad. In 1941, the Red Cross launched a national blood donation program for the U.S. military and supported American military personnel and their families during the Korean War, Vietnam War, and Middle East conflicts, as well as assisting disaster victims, including Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the 2010 Haiti earthquake, and Hurricane Sandy in 2012.