In recent decades, technological advancements, particularly the rise of the internet, have connected people around the world like never before. A person in the far-western United States can now easily communicate daily with someone in far-eastern Japan without any issues. Today, it’s rare to find a place on Earth that remains isolated, with a few exceptions such as remote tribal groups living on isolated islands that have yet to keep pace with global changes. One such group is the Sentinelese tribe, who have lived in isolation on their island for nearly 60,000 years and have steadfastly refused any attempts at contact from outsiders. Over the past 200 years, many outsiders have visited the island trying to meet its inhabitants, but these encounters have often ended poorly and sometimes tragically for both parties involved.

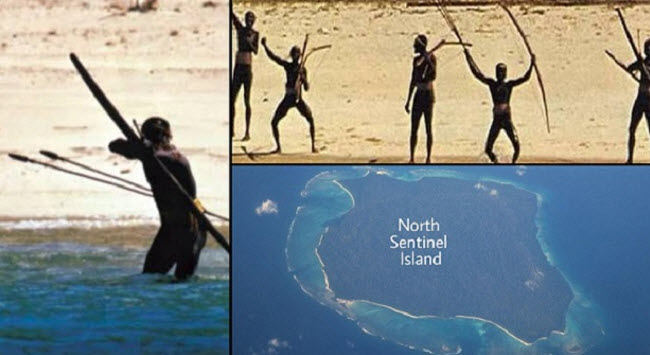

The Sentinelese live on a remote island off the northwestern tip of Indonesia, which is part of a small archipelago of more than 570 islands across the deep blue waters of the Bay of Bengal, known as the Andaman Islands. Despite most of these islands being open to tourism and inhabited for centuries, North Sentinel Island remains an exception. Tourists are warned to stay away to avoid aggressive actions from its residents. Even nearby Andaman Islanders avoid sailing near its waters to prevent conflicts, as interactions with the Sentinelese are difficult to handle diplomatically. The tribe’s self-imposed isolation means no one outside their shores speaks their language, and similarly, they do not speak any other language, making translation and communication virtually impossible.

Stories of Sentinelese aggression date back to when an Indian merchant ship called the “Ninoy” ran aground on the coral reefs. Eighty-six passengers and twenty crew members swam to shore and stayed for three days before the Sentinelese decided they had overstayed their welcome. The tribe used bows and arrows to drive them away, and the survivors fought back with sticks and stones until a Royal Navy ship arrived to rescue them. In 1896, a convict on the run from the Great Andaman Islands colony attempted to escape in a boat and reached North Sentinel Island, only to be found dead a few days later with arrow wounds and a slashed throat. More recently, in 2006, two Indian fishermen, Sunder Raj and Bandit Tiwari, were hunting crabs near the island despite knowing the dangers. They were attacked and killed by the Sentinelese when their boat drifted too close to the forbidden shore. The Indian Coast Guard was not allowed to retrieve the bodies and was instead met with a barrage of arrows from the tribe. Efforts to recover the bodies were abandoned, and the tribe remained isolated once again. Over the next 12 years, no further contact attempts were made.

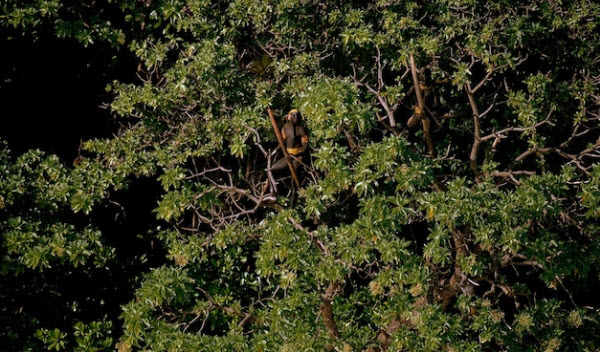

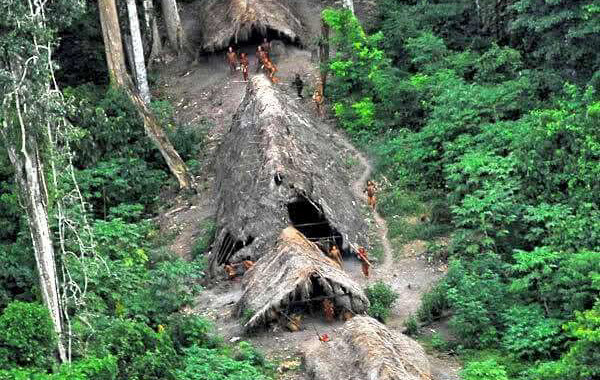

The actions of the Sentinelese are unsurprising given their nearly 60,000-year history of avoiding outsiders and dealing with them. The island’s terrain contributes to their isolation, as it lacks natural harbors, is surrounded by sharp coral reefs, and is almost entirely covered by dense forest, making any journey to the island extremely difficult. Little is known about them; estimates of their population are challenging, but experts believe it ranges from 50 to 500 individuals. Observations from afar show that their homes are simple palm-thatched huts arranged in clusters facing each other, with carefully tended fires outside each. They build narrow, small boats with extended arms to maneuver through the relatively shallow, calm waters inside the coral reefs. How they have survived over the years, especially after the 2004 tsunami that devastated the Bay of Bengal, remains unknown. Despite seeming to lack tools from outside the island, researchers have noted that they use metal objects washed ashore from shipwrecks or passing vessels. Even their arrows, used against unfortunate helicopters attempting to land, feature various tips for hunting animals, fishing, and self-defense.

Despite their isolation, the Sentinelese have drawn attention over the centuries with attempts to make contact. The first recorded attempt occurred in 1880 when British explorer Maurice Portman, age 20, abducted an elderly couple and four children from North Sentinel Island. His intention was to bring them to the UK, treat them well, study their customs, shower them with gifts, and then return them to the island. However, upon reaching Port Blair, the Andaman Islands capital, the elderly couple fell ill due to their weakened immune systems against outside diseases. Fearing for the children’s lives, Portman and his men returned them to the island. The tribe remained isolated for nearly 100 years until 1967 when the Indian government attempted contact again, but the tribe retreated into the jungle whenever Indian anthropologists tried to engage with them. Researchers eventually decided to leave gifts on the shore and retreat. Further contact attempts were made in 1974, 1981, 1990, 2004, and 2006 by various groups of researchers, including a National Geographic team, which came by a naval sailing ship and the Indian government, but all were met with a relentless barrage of arrows. Since 2006, after the efforts to retrieve the bodies of the Indian fishermen, only one more contact attempt was made, which also ended in tragedy.

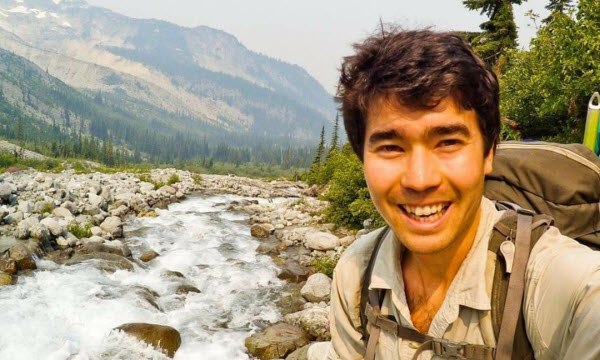

The most recent attempt was made by American adventurer John Allen Chau, 26, who was always eager for adventure but often found himself in trouble. Unfortunately, his adventurous spirit led him to North Sentinel Island, where he was drawn to its isolated shores with great enthusiasm. Despite knowing the Sentinelese had violently rejected previous contact attempts, he felt compelled to make a greater effort to communicate with them. In the fall of 2018, he traveled to the Andaman Islands, convinced two fishermen to help him evade patrol boats, and made his way to the forbidden waters. When his guides refused to go further, he swam to the shore alone, encountering some tribe members who were not welcoming. The women of the tribe spoke anxiously among themselves, and when the men appeared, they were armed and hostile. Chau quickly returned to the waiting fishermen and made a second trip the next day, this time bringing gifts including a soccer ball and fish. A teenage member of the tribe shot an arrow at him, hitting one of the gifts he carried. Realizing the danger of his third visit, Chau wrote in his journal, “The sunset is beautiful, and I wonder if it will be the last one I see.” Tragically, when the fishermen returned the next day to retrieve him, they found the Sentinelese dragging his body away for burial. His remains were never recovered, and the fishermen who helped him were arrested.

Chau’s actions sparked international debate over the value and risks of his endeavor, as well as the protected status of North Sentinel Island. Some argued that while Chau intended to help the tribe, he actually endangered them by introducing potentially harmful germs, while others praised his bravery but were disappointed by his failure to recognize the slim chances of success. Critics viewed the visit as disruptive, reaffirming the tribe’s right to maintain their beliefs and practice their culture in peace—rights lost by nearly every other island in the archipelago due to European colonization.