The Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union (now Russia) did not confine its rivalry to Earth alone; it extended into space. Both superpowers were engaged in a frantic race, with each side eager to reach the Moon first. In the early days of the space age, Soviet achievements were notably superior, leaving Americans feeling frustrated. In response, U.S. officials sought any means—even a dramatic one—to prove they were still in the race. This led to the creation of a bold and controversial plan known as Project A119. The project aimed to detonate a nuclear thermonuclear weapon on the Moon, hoping to showcase this explosion to the world and send a clear message that America was still a formidable force, capable of reaching the Moon, even if not through scientific means but through military might.

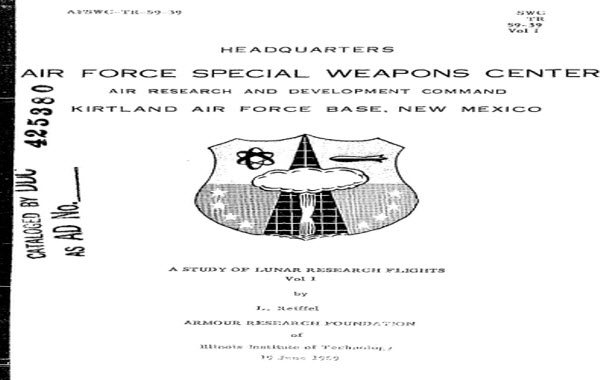

The story of Project A119 begins in the years immediately following World War II. Dr. Leonard Reiffel enjoyed working alongside the legendary physicist Enrico Fermi at the University of Chicago’s Institute for Nuclear Studies. However, in 1949, he was given the opportunity to oversee advanced physics research at a different facility in the same city, the ARF Research Institute (now known as the Illinois Institute of Technology). By 1962, Reiffel and his colleagues were focused on studying the global environmental impacts of nuclear explosions. Yet, before May 1958, the U.S. Air Force tasked this team with an unusual assignment: to conceptualize the effects of a hypothetical nuclear explosion on the Moon. The goal was to surprise the Soviets and the world by transforming the Moon into a spectacle of fiery destruction.

Realizing he lacked the expertise for such a study, Dr. Reiffel enlisted additional scientists, including Gerard Kuiper, a planetary physicist known for his work on the Kuiper Belt—a region beyond Neptune filled with icy bodies and comets. To complete the team, Kuiper suggested bringing in a young graduate student from the University of Chicago named Carl Sagan. Sagan, who later gained fame as a beloved science communicator with his popular TV show “Cosmos,” was tasked with the mathematical modeling of the dust cloud resulting from the nuclear explosion on the Moon. It was crucial to understand the Moon’s reaction to determine whether the explosion would be visible from Earth, as the primary objective of the project was to maximize visibility.

Project A119 raised two significant questions: Why would self-respecting scientists agree to a project involving a nuclear explosion on the Moon? And would the U.S. have the capability to deliver the bomb and accurately assess the explosion’s impact on the lunar surface? To address the first question, one must consider the context of late 1950s and early 1960s America, where science was deeply intertwined with Cold War politics. Despite the end of the McCarthy era, scientists were acutely aware of the public disgrace faced by atomic bomb developer Robert Oppenheimer for opposing the creation of the more powerful hydrogen bomb. Fear was not the only motivator; many scientists were driven by patriotism and a sense of duty to protect their country, while others were war refugees who had escaped tyranny and viewed their work as part of a broader struggle for the free world.

Beyond ethical considerations, many involved in Project A119 saw potential for significant scientific discovery. Carl Sagan, who dedicated his life to searching for evidence of extraterrestrial life, saw the project as an opportunity to detect microorganisms or organic molecules on the Moon alongside lunar dust. Other scientists anticipated the project could provide insights into lunar chemistry and thermal conductivity. There was also curiosity about whether the nuclear explosion might generate sufficient seismic activity to evaluate the Moon’s internal structure.

As for the delivery of the nuclear bomb to the Moon, it was clear that the U.S. had early ballistic missile technology. Reiffel later revealed that they could have accurately targeted the Moon with a margin of error of just a few miles—a significant achievement considering the Moon’s distance of approximately 384,400 kilometers from Earth. Regarding the formation of a nuclear mushroom cloud, the plan was to detonate the bomb on the Moon’s far side, where sunlight would silhouette the explosion’s cloud. However, extensive studies revealed disappointing results. The absence of an atmosphere on the Moon meant there would be no resistance to the expansion of dust and debris, resulting in no visible mushroom cloud, sound, or shockwave—just a vast amount of dust. Nonetheless, the explosion could still create a visually striking or frightening display akin to a sunrise through the debris.

Despite the efforts invested in Project A119, it was ultimately canceled for unclear reasons. Current speculation from various informed sources suggests that the Air Force may have canceled the program due to potential risks to Earth’s population if the mission failed catastrophically, similar to early American spaceflight attempts. Others believe scientists were concerned about contaminating the Moon with radioactive materials, which could hinder future manned missions or colonization. Another possibility is that public backlash over the perceived desecration of the Moon’s beauty outweighed scientific and strategic considerations, though this is less likely given the Air Force’s priorities.