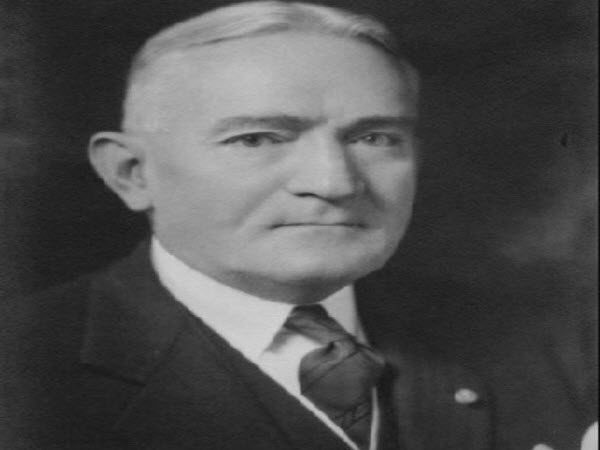

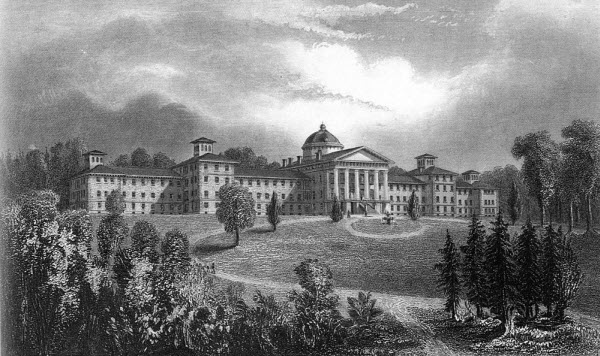

The advancement of science, especially in the medical field, owes much to the studies and experiments conducted by scientists in the past. These discoveries and theories, some of which may have been stumbled upon by chance and others achieved through seemingly outrageous experiments, have propelled humanity forward. One such extraordinary case occurred in the early 20th century in the United States, led by an American doctor named Henry Cotton. Over 26 years, Cotton performed more than 645 unusual operations at Trenton State Hospital, attempting to cure mental illness by extracting patients’ teeth. He was convinced that mental illness was merely a result of untreated bodily infections, which led him to conduct these bizarre experiments to validate his theory. His methods left many wondering who the real madman was—the patient or the doctor.

When Dr. Henry Cotton began managing Trenton State Hospital in New Jersey, he started removing his patients’ diseased teeth based on his medical beliefs. However, to his dismay, this did not always cure them of their insanity. In fact, their conditions often worsened, as the surgeries left them unable to speak clearly or eat properly. Instead of acknowledging the flaws in his treatment approach, Cotton concluded that the reason his surgeries were not successful was because the infections had spread too far in the body. Consequently, he extended his procedures to include the removal of other infected parts, such as the tonsils, stomach, gallbladder, testicles, ovaries, and colon—or so he claimed. Cotton reported that he had successfully treated 85% of his patients. Naturally, his colleagues admired and enthusiastically adopted his methods, and parents of mentally unstable children were eager to secure a spot in his busy schedule. If that was not possible, they insisted that their doctors perform similar surgeries.

Strangely, Henry Cotton became famous and was recognized for his successful treatments of insanity both in America and Europe, despite the high mortality rate among his patients. At one point, one in three patients died following Cotton’s treatment. This alarming rate led many patients to realize the dangers of his surgeries and refuse to go to the operating room, often being dragged there against their will. As the mortality rate increased to 30%, Cotton began to acknowledge the looming danger but claimed it was due to most patients being in poor physical condition.

Fortunately, not all doctors were enchanted by Cotton’s methods. Some psychiatrists were skeptical of his surgeries, and numerous allegations surfaced suggesting he mistreated his patients. Cotton managed to placate his critics by replacing his male nursing staff, whom he was accused of mistreating, with female nurses. The New York Times commented on this change, suggesting that men were typically too harsh with patients, and Cotton believed that having female nurses would be much more comforting for the patients.

These practices continued for 26 years, and by 1924, a proper investigation into Henry Cotton’s medical methods began, led by Dr. Phyllis Grenaker. She had an intuition that something was wrong with the doctor and his procedures, especially after observing the harmful environment of the hospital. Grenaker found the hospital records disorganized and Cotton’s data inconsistent. To dig deeper, she interviewed 62 of Cotton’s former patients, uncovering horrifying stories. She discovered that seventeen patients had died immediately after Cotton’s surgeries, while others suffered for several months before eventually dying. These deaths were not included in the records. Further results revealed that only five patients had fully recovered, three others showed some improvement, but their symptoms persisted, and the rest saw no improvement.

These findings made Dr. Grenaker even more suspicious. She reached out to former patients who had left the hospital, supposedly cured or improved, only to find that they remained mentally unstable. Concurrently with Dr. Grenaker’s investigation, a Senate committee in New Jersey was formed to examine the situation at the hospital. During the investigations, Henry Cotton suddenly feigned insanity. Over time, Grenaker’s report was ignored, and the Senate lost interest in the investigations. Cotton miraculously avoided accountability, claiming that he had recovered from his own mental crisis by removing some of his infected teeth, and even went so far as to extract the teeth of his wife and children for preventive measures.

The demand for Henry Cotton’s treatments persisted. Not only did he continue his surgical practices at Trenton State Hospital, but he also traveled across the United States and Europe to give lectures and opened his own private clinic, welcoming wealthy patients desperate to cure their loved ones. By the 1930s, he retired and became an honorary director, though this did not stop him from continuing his surgeries. He even developed a new, more extreme idea, believing it was beneficial to perform colostomies on children to prevent insanity and deter them from engaging in bad habits like masturbation. He also criticized dentists, believing their work in repairing teeth was futile compared to simply extracting them.

In the 1930s, new investigations by the hospital board, medical institutions, and government agencies in New Jersey examined the records of 645 patients who underwent Cotton’s procedures and compared them with 407 patients who did not. They found that the recovery rate was higher among those who had not been treated by Cotton. Unsurprisingly, Cotton and his supporters fiercely contested claims that their surgeries were harmful. Amidst this final battle, Cotton died of a heart attack in 1933. Patients at Trenton State Hospital breathed a sigh of relief, as records showed that Cotton and his assistants had extracted over 11,000 teeth and performed 645 major surgeries, causing death or severe disfigurement to hundreds of individuals. Despite this, an obituary in The Times lamented the loss of this “great pioneer,” whose human impact would remain among us.