From a young age, we grew up on tales of Tarzan, the boy left in the jungle to be raised by animals. Through his upbringing, he began to adopt their behaviors. In reality, there have been documented cases around the world that support this idea. This has prompted some scientists to wonder what would happen if the opposite approach were taken—bringing an animal from a young age and integrating it with human companionship. Would the result be that the animal adopts human behaviors, or is behavior innate and tied to genetics?

Given the lack of a definitive answer, it was essential to test this concept practically through a unique experiment conducted by a pair of psychologists in the early 1930s—Winthrop and Luella Kellogg. They decided to adopt a baby chimpanzee named Gua and allow it to live with them alongside their own infant, Donald, and observe the outcomes.

The experiment began two years before it was practically conducted. Winthrop Kellogg earned his doctorate in psychology from Columbia University and taught at Indiana University in the United States. Early in his career, he was fascinated by the idea of “wild children” growing up in untamed environments. He had many questions about what an individual would be like if they grew up without human language, clothing, or connections with other humans. Although there were a few cases of wild children allegedly emerging from the forest, these were not sufficient scientifically to answer a major question in psychology at the time: Is nature or nurture the primary factor in shaping an individual’s life?

This question was the driving force behind the 1931 experiment, conducted during the height of the eugenics movement, which claimed that mental and intellectual deficiencies were always natural and hereditary, not acquired. This ideology was reinforced in 1927 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that mentally disabled individuals could be forcibly sterilized. The purpose of the chimp and child experiment was to refute this theory by demonstrating that environment was more crucial than genetics and that upbringing was key to influencing personality.

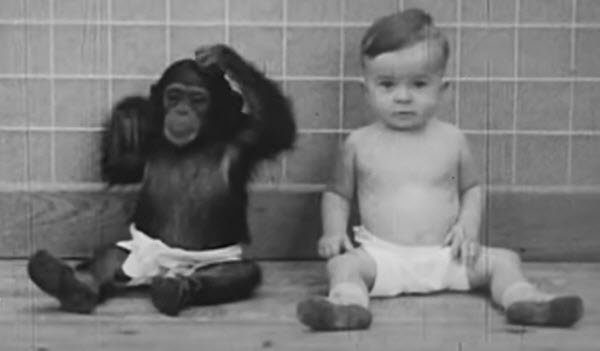

The experiment aimed to determine if a chimpanzee could develop human-like traits if raised in a human environment. Gua, a 7.5-month-old female chimpanzee from Cuba, was introduced to the Kellogg family and placed with their 10-month-old son, Donald. They were treated as siblings, dressing alike, undergoing the same training, eating the same food, and participating in the same activities. The entire process was closely monitored by the Kelloggs and other researchers, who made detailed comparisons and documentation.

As part of their observations, Gua and Donald underwent regular tests to monitor various factors, especially intelligence and behavior. The results were somewhat surprising to the Kelloggs. Initially, Gua displayed higher intelligence than Donald, regularly outperforming him in tests. She began walking upright and using utensils while developing facial expressions similar to humans. Meanwhile, Donald struggled to keep up with Gua. However, many considered Gua’s advanced abilities natural, given her wild upbringing, which required intelligence for survival. In contrast, human infants are helpless until they reach a certain level of cognitive development.

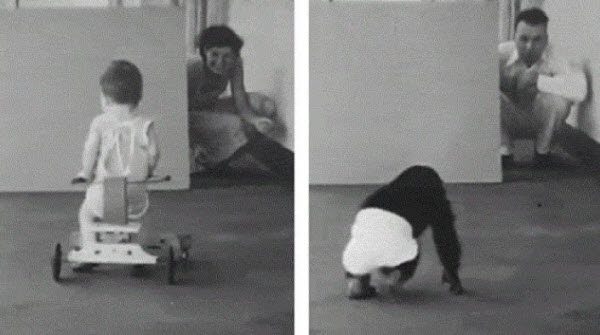

After their first year, Donald began to gain an advantage over Gua as language started playing a role in his growth and development, making performance tests easier for him. However, Gua continued to excel in physical activities like running and climbing. The Kelloggs anticipated that Gua wouldn’t suddenly speak like a human just because she lived among humans, but they hoped she might begin to mimic human speech. This did not happen. Instead, they noticed something more intriguing: Donald began to imitate Gua’s behaviors and sounds. He started wrestling with Gua in ways resembling chimpanzee play rather than typical child interactions. He learned to spy on people under doors and even began to bite and crawl like a chimpanzee, continuing these behaviors even after learning to walk. This imitation raised concerns that Donald might end up more influenced by chimpanzee behaviors than developing human traits. Fearing that Donald might grow up more like a chimpanzee than Gua would become human, the Kelloggs decided to end the experiment after nine months.

Upon concluding the study, the Kelloggs documented their findings in a book titled “The Ape and the Child.” Fortunately, the experiment was approved at the time. A similar experiment conducted today might provoke concern among scientists, animal rights activists, and child protection services. As for Gua, she was returned to the primate center from which she had been adopted. Unfortunately, she died less than a year after being separated from her “sibling” due to pneumonia. Despite her death, her contributions to psychology remain significant, and this unique experiment is still recognized and valued today.