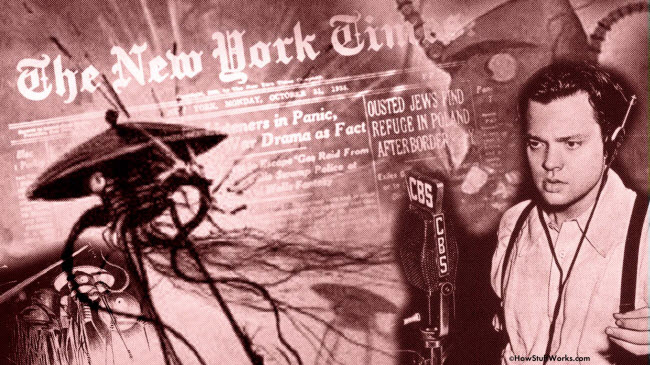

On the morning of Halloween in 1938, the 23-year-old Orson Welles woke up to find his name and photo plastered across the front pages of newspapers and magazines throughout the United States. He had become the talk of the nation due to the chaos that ensued following his radio broadcast of H.G. Wells’ novel “The War of the Worlds” on CBS the previous night. The broadcast featured segments formatted as news bulletins describing a Martian invasion of New Jersey, which led many listeners to believe that the events were real, causing widespread panic and hysteria.

Welles barely had time to glance at the newspapers, which reported mass hysteria, including people fleeing their homes, committing suicide, and general chaos in the streets. People were so outraged that some even threatened to kill him on sight for the panic he had caused. At that moment, Welles’ career and even his personal freedom seemed at risk. He reportedly told several people, “If I had planned to wreck my career, I couldn’t have done it better than this.” In a hastily arranged press conference at the CBS building, surrounded by dozens of reporters and photographers, Welles apologized for the unintended consequences of his broadcast. The primary question on everyone’s mind was whether he had done it deliberately or if it was a spontaneous mistake.

The expected answer at the time was, of course, a denial of any intention to deceive to avoid responsibility and escape punishment. However, years later, when memories of the incident had faded and the script drafts for the episode were revisited, it became clear that no one involved had anticipated such a strong reaction. The cast and crew had believed it would be hard for listeners to take the story seriously, as they found the plot too absurd to be convincing. Nonetheless, in an attempt to make the broadcast more engaging, they decided to start the show in the middle of the story, right at the beginning of the invasion, without any lead-in or introduction.

The story began in late October 1938 when actor and director Orson Welles and his troupe were contracted by CBS to produce a radio program featuring dramatized adaptations of world literature for 17 weeks. The program was low-budget and lacked sponsors due to its relatively small audience. With Halloween approaching, Welles wanted to present something entirely different from previous shows. He chose “The War of the Worlds,” a novel depicting a Martian invasion of early 20th-century Britain, where the Martians easily defeat the British army with their advanced weapons, including “heat rays” and toxic “black smoke.” The story ends with the Martians succumbing to Earth’s diseases, against which they have no immunity. Welles made some modifications to the story to make it more realistic, relocating the invasion from Britain to various cities in the United States. He tasked writer Howard Koch with adapting the novel into a radio drama, although Koch was initially reluctant and tried unsuccessfully to persuade Welles to choose a different story.

The broadcast aired on Sunday, October 30, at 8:00 p.m. on CBS. This was the peak of radio’s golden age, a time when millions of Americans tuned in to listen. However, most of them were listening to a popular comedy show on NBC and didn’t switch over to Welles’ program on CBS until 8:12 p.m., after the comedy show had ended. By then, the Martian invasion and its events were already unfolding.

Welles’ direction of the episode was genuinely terrifying. It began with an introduction read by an announcer, followed by a weather report, before transitioning to the Meridian Room at the Park Plaza Hotel in New York City, where a live orchestra was playing. The calm was soon interrupted by a news bulletin announcing that Professor Farrell had observed explosions on Mars. The music resumed, only to be cut off again by a report that a large meteor had crashed into a farmer’s field in New Jersey. A reporter on the scene described a Martian emerging from a large metal cylinder within the meteor, saying, “Good heavens, something’s wriggling out of the shadow like a gray snake. Now here’s another one, and another one, and another one! They look like tentacles to me. I can see the thing’s body now. It’s large, large as a bear, and it glistens like wet leather. But that face… it… it… ladies and gentlemen, it’s indescribable… I can hardly force myself to keep looking at it, it’s so awful. The eyes are black, and they gleam like a serpent. The mouth is V-shaped, with saliva dripping from its rim.” The broadcast continued, describing how the Martians rode their war machines and fired “heat rays” at the gathering crowd, killing them and destroying a National Guard force of 7,000. After being bombarded with artillery and bombers, the Martians released a poisonous gas into the air, as more Martian ships landed in Chicago and St. Louis.

The radio drama was so realistic that it created a significant panic among listeners who only heard part of the broadcast and believed it to be true. Many rushed to contact others to warn them, intensifying the spread of fear. Numerous people called the police, CBS, and newspapers to confirm the news and seek advice on how to protect themselves from the invasion. The New York Times reported that many people needed treatment for shock following the hysteria. Traffic jams occurred as people tried to flee their homes and leave New York City. Communications were disrupted due to the overload, and more than 20 families fled their homes with wet towels and rags over their faces, fearing a gas attack. The Providence Journal reported that many women called the paper for more details about the massacre, while the Associated Press noted that a man returned home mid-broadcast to find his wife holding a bottle of poison, saying she would rather die that way than fall into the hands of the Martians.

Due to the hysteria, CBS network supervisor Davidson Taylor received a phone call during the broadcast, after which he returned to the control room pale as a ghost. He was ordered to interrupt the broadcast immediately and announce that the program was fictional. Later, police entered the station, and after the episode ended, they began escorting the actors out of the studio and detained them. The press surrounded the building, and the actors were eventually released through the back doors. Over the next three weeks, newspapers published at least 12,500 articles about the broadcast and its impact. Even Adolf Hitler referenced the broadcast in a speech he gave in Munich in November 1938, citing it as evidence of the corrupt and deteriorating state of democracy.

In the wake of the uproar, the Federal Communications Commission investigated the broadcast but found that no laws had been broken. However, it did issue a recommendation that stations be more careful in their future programming. While the incident initially harmed Orson Welles’ reputation, it ultimately helped him secure a contract with Hollywood studios. In 1941, he directed, wrote, produced, and starred in the film “Citizen Kane,” which many have described as the greatest American film ever made.

Despite the extensive coverage of the panic in newspapers, some have questioned the extent of the hysteria, suggesting that the reactions may have been exaggerated. Critics point out that there is no evidence of hospitals being overwhelmed by patients as a result of the broadcast, and some argue that newspapers may have amplified the incident in retaliation against the radio industry, which was beginning to overshadow print media by portraying it as a medium that spreads false news and incites public fear.