Chess is often regarded as one of the greatest intellectual games, and while many people play it, only a few achieve the title of Grandmaster or win international championships. For a long time, men dominated the game, but Hungarian player Judit Polgar changed that dynamic and put women on the chess map. Thanks to her dedication and genius, she earned the title of the greatest female chess player of all time. Her rise to prominence can be credited to one person: her father, Laszlo Polgar, who began training her and her sisters from a young age. He believed that if children are taught early, they could become geniuses in any field.

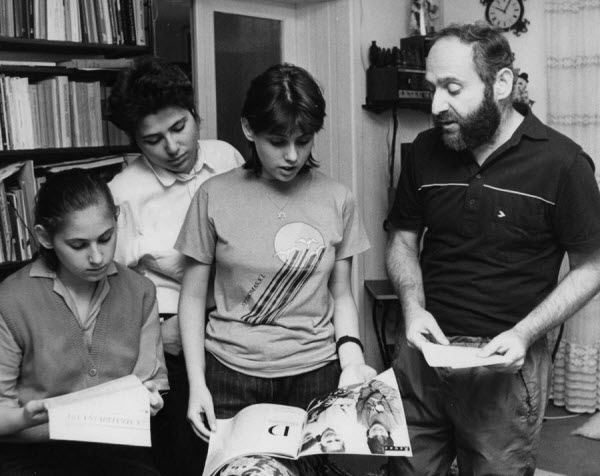

Laszlo Polgar, a teacher by profession, approached fatherhood with an academic focus. He convinced his future wife, Clara, a Ukrainian language teacher, of the great educational mission he envisioned. He intended to raise prodigies and prove that genius is cultivated through time and training, not innate. Clara agreed with his plans, and they married, living initially in the Soviet Union before moving to Laszlo’s hometown in Hungary. They began planning the future of their daughters, Susan, Sofia, and Judit Polgar. Their strategy, based on years of research, was clear and direct: to educate their children at home, a choice that puzzled local residents and authorities at the time.

For Laszlo, there was no other option. His research convinced him that to raise prodigies, he needed to start teaching them before they turned three and specialize by the age of six. This specialization didn’t necessarily have to be in chess, but to ensure success, his children had to excel in any field. Clara planned to teach them languages (Russian, English, German, and Esperanto) alongside advanced mathematics. However, the eldest sister, Susan, chose chess due to her love for the small game pieces. This choice set the path for her and her sisters’ future. The parents had no objections since chess was a good choice for specialization, as success could be measured precisely through international chess rating systems.

Judit Polgar, born in 1976, was the youngest of her sisters. She knew her childhood seemed unusual and acknowledged that many assumed her life and her sisters’ lives were bleak. However, for her, it was the opposite. Surrounded by already exceptional siblings in chess, Judit was eager to learn. Chess became a family activity that bound them together in a society that was skeptical of their pursuits. They were frequently subjected to attacks, criticism, and doubts. Many questioned whether women could truly excel in chess, considering it a mental game and claiming women simply weren’t as intelligent as men. Her father, Laszlo Polgar, refuted this, insisting that the issue was a lack of proper training and that with enough practice, women could play just as well as men, if not better. This was a notion that proved true over time.

Judit Polgar practiced chess daily for five to six hours. By the age of five, she had already beaten her father, and at fifteen, she became the youngest person ever to be awarded the Grandmaster title, the highest title in chess. She dominated women’s-only tournaments but found the competition lacking in challenge. She agreed with her father that most women hadn’t been trained adequately to challenge opponents and wanted to test her skills at the highest levels, meaning competing against male players who dominated the chess world.

Although Judit Polgar aimed to compete with men, her sister Susan broke that barrier in 1986 by becoming the first woman to qualify for the men’s world championship and shortly thereafter earned the title of Grandmaster. Judit quickly followed in her footsteps, though their success did not always resonate well with older male players who routinely defeated them. Susan noted that some male players never admitted to being beaten by a woman and always found excuses for their losses, such as claiming a headache or stomach pain.

Even as Susan and Judit Polgar rapidly ascended the global rankings, many of the world’s top players still doubted that women could truly compete at the same level as men. Garry Kasparov, the world’s top-ranked player, commented on Judit: “She is talented, but not exceptionally so, as women are not naturally extraordinary chess players.” In 1994, Kasparov had the opportunity to test Judit Polgar’s skills firsthand. During their match, a controversial moment occurred when Kasparov moved his knight but then retracted the move after reconsideration. According to the rules, once a player releases a piece, the move is final. Despite this, the referee allowed Kasparov to retract the move, and he eventually won the game.

Despite the bitter loss to Kasparov, Judit Polgar’s determination remained unshaken. By the following year, she was ranked as the tenth-best player in the world and continued to play chess professionally for a few more years. In 2005, she was ranked eighth globally and met Kasparov 17 times during this period, winning one match and drawing four. After giving birth to her child in 2006, she decided to step back from competitive play, citing a shift in priorities to writing books, organizing chess events, and raising her daughter. She described these activities as balanced and offering a new perspective on life.

Even with these new pursuits, Judit Polgar never lost interest in chess. She continued to participate in tournaments until her retirement in 2014. To this day, the chess world remembers the contributions of Judit and her sisters. Although Judit Polgar is no longer the highest-ranked woman in chess, she remains an inspiring example for any woman who loves the game and seeks to excel, competing with men in the rankings.