Mars has always captivated human interest due to its proximity to Earth and its similarities to our planet. So much so that many astronomers refer to it as Earth’s twin. Despite being observed for thousands of years with the naked eye, telescopes, and more recently, space probes, Mars remains elusive when it comes to human exploration. Although much has been learned about it in recent years, the planet still holds many intriguing secrets that drive the quest to answer the question on many minds: Could there be life on Mars, especially considering some indicators suggesting it might have hosted intelligent life in the past?

Throughout history, Mars has been linked with numerous ancient cultures, appearing in texts as a fiery star or a god of war. In the 17th century, early telescopes allowed scientists to glimpse the red planet. As more advanced telescopes emerged, astronomers began to scrutinize Mars’s surface more closely, leading to theories about the existence of life on the planet. One such theory emerged in 1877 when Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli observed intersecting lines on Mars’s surface, which he named “canali,” meaning “channels.” While Schiaparelli was skeptical that these channels indicated extraterrestrial life, others disagreed, believing that such structures could only be the result of intelligent beings creating a vast network of waterways.

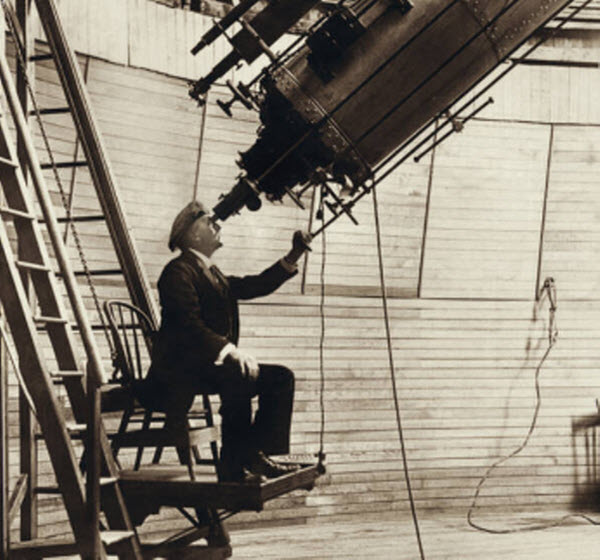

Some theories went beyond suggesting that the channels were created by intelligent life; they posited that they were constructed under the guidance of skilled engineers. For instance, the construction of the Suez Canal on Earth took ten years to complete in 1869. Comparatively, what was observed on Mars seemed far more complex. This was the belief of astronomer Percival Lowell in 1894, who used his family’s wealth to establish the Lowell Observatory in Arizona. There, he expanded his study of Martian channels, creating detailed maps and writing extensively on his theory of Martian life. Lowell drew parallels with life on Earth, noting that just as submarines revealed previously unknown sea life, Martian life could exist below its surface, adapting to harsh conditions.

In 1899, Lowell’s theory received support from the prominent inventor Nikola Tesla, who, while conducting experiments with a high-altitude transmitter in Colorado Springs, detected a faint, unexplained signal he attributed to Mars. Tesla claimed the message was from a distant world, with its content being “one-two-three.” A few years later, during an interview in February 1901, Tesla suggested that wireless messages could be sent to Mars with precision and expressed his belief in Martian life. Although unsure of what Martian life forms might look like, Tesla was convinced they had adapted to the planet’s extreme conditions, similar to Lowell’s theory that intelligent beings might live underground rather than on the surface.

Years later, in 1909, several attempts were made to establish contact with Martian life. One such idea came from Harvard professor William Henry Pickering, who proposed sending light signals to Mars through a network of 50 giant mirrors. The flashes would last several years, allowing Martians time to develop means to respond. Pickering reasoned that if there was life on Mars, its inhabitants likely had telescopes and eyes, and would respond similarly to Earth’s signals. However, the project faced a major obstacle: funding, as the cost was 10 million dollars, an enormous sum at the time. Another proposal by Robert Wood of Johns Hopkins University involved covering Nevada’s white alkali plains with large black patches made from 10 square kilometers of fabric. This plan was also thwarted by a lack of funding. Despite the setbacks, scientist David Todd proposed using a hot air balloon to send messages from an altitude of 15.2 kilometers, believing Martians might be trying to communicate with us using methods we had not yet noticed. His balloon reached only 1.5 kilometers before support from the War Department was cut.

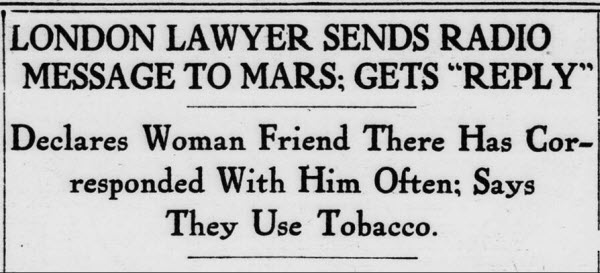

Although previous attempts using radio, mirrors, hot air balloons, and even massive black patches to communicate with potential Martian life ended in failure, they were grounded in scientific methods. In contrast, in October 1926, British lawyer Hugh Mansfield Robinson from London tried to send a direct telegram to Mars, claiming that his Martian friend awaited him there. Robinson, confident in receiving a reply, chose this time because Mars was closest to Earth. He claimed his Martian friend, named “Omaruru,” was 1.8 meters tall and lived with fellow Martians who, like Earth’s inhabitants, drove cars, smoked pipes, and soared through the sky in electric balloons. Despite the oddity of his request, the telegram was sent from Rugby Tower, the world’s strongest wireless station at the time. Although no response was received, Robinson claimed he heard from Omaruru that Martians had waited hours to receive his message.

While earlier scientific ideas may have seemed far-fetched, they inspired future generations. By 1976, NASA was actively searching for life on Mars using two Viking spacecraft. One experiment yielded positive results, suggesting that some form of life may have once consumed nutrients present in the soil, hinting at the possibility of life on the red planet. However, these findings remain debated today. Subsequent explorations provided evidence that Mars might have been habitable in the past. For example, in 2012, a mountain on Mars called “Gale” was discovered, rising five kilometers and composed of sedimentary rocks with layers of different minerals believed to have been formed by wind and water, essential elements for life. Scientists theorize that if Mars had an atmosphere, microbial life might have existed billions of years ago as these layers formed, and the planet could have been habitable about a million years ago.

To date, there is no confirmed evidence of life on Mars. The scientific community awaits further discoveries, whether through new, advanced probes or by taking steps towards colonizing the planet to uncover its mysteries and secrets.