With the increasing passion for space travel and the discussion about the idea of creating space colonies, coupled with cinema’s portrayal of these visions in films, many people are raising questions about this topic. Specifically, questions are being asked about how medical care will be managed in areas where there is no gravity. For example, can a surgical operation be performed in space, given that such operations require certain conditions to be successful, including that the patient is anesthetized and immobilized to allow surgeons to work without any hindrance? These are questions we will address in this article.

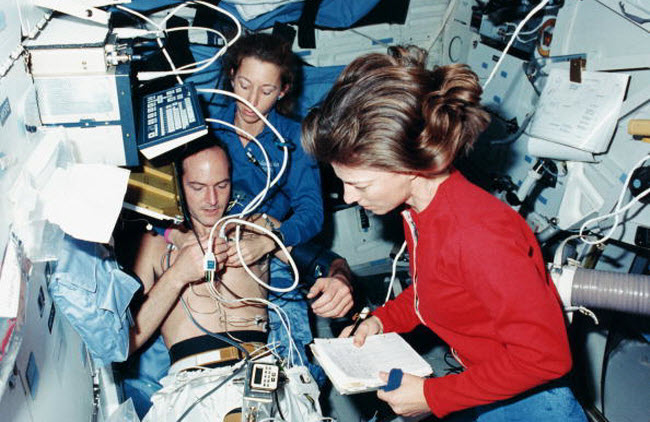

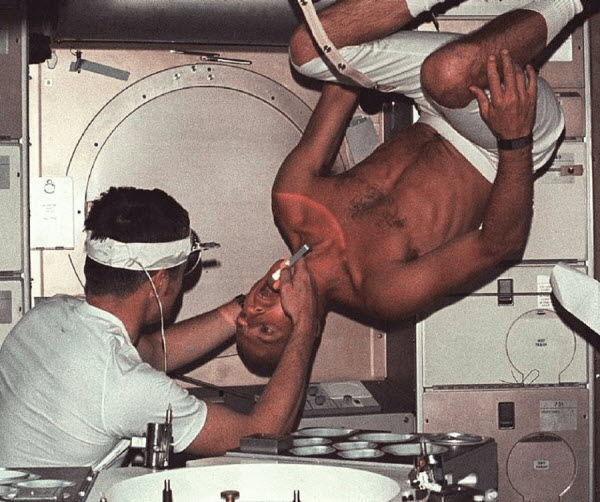

To begin with, medical emergencies in space are still extremely rare. No astronaut has undergone surgery in orbit or beyond, whether on missions to the moon or during the continuous occupation of the International Space Station (ISS). However, these concerns are taken very seriously to avoid any potential issues. Astronauts are trained in some basic first aid skills, such as stitching wounds, pulling teeth, and administering various injections. These procedures help alleviate common medical problems encountered by astronauts, such as motion sickness, burns, and general aches and pains. Generally, astronauts selected by NASA are in excellent health, having passed a series of rigorous medical tests that determine their suitability for living in space.

Regarding performing surgery in space, NASA has indeed been concerned about this issue. In 1991, retired astronaut Mark Campbell attempted to perform surgery on a rabbit inside a gravity-free simulator known as “vomit comet”—a training chamber where astronauts experience microgravity for 25 seconds, which is why it is named after the vomiting it can induce. Campbell stood floating over an operating table with a rabbit lying on it, restrained and under anesthesia. When he cut into the rabbit’s carotid artery, he observed that the blood flowed upwards in bubbles before stopping, and then it began to clump together, forming a wobbly dome over the wound, similar to jelly. Campbell then tried cutting another artery, and the result was the same. He concluded that blood behaves differently in microgravity than expected, expressing his frustration that the bleeding did not occur as anticipated. He found that proceeding with surgery in space is extremely difficult due to the unique challenges of a zero-gravity environment, such as maintaining a sterile and safe environment.

Despite these difficulties, some alternatives are being considered for medical emergencies in the International Space Station. The Russian Soyuz capsule docked at the station, which serves as a sort of lifeboat, can return astronauts to Earth within 24 hours. However, this return is not straightforward and can subject the injured or ill astronaut to harsh Earth-bound conditions, making the situation even more challenging.

Another issue with performing surgery in space is related to anesthesia. Since anesthesia is usually administered through inhalation, there is a risk that some of it may leak due to microgravity, potentially affecting the other astronauts. Therefore, space medicine is limited to injectable or ingestible medications only. The effectiveness of these medications under harsh space conditions remains uncertain. Additionally, traditional medical equipment, such as diagnostic imaging tools, is too large to be launched into space, making the development of smaller equipment crucial. Currently, there are no viable solutions for performing surgery in space, except for waiting for a technological breakthrough, possibly involving robotic surgery or advancements in remote surgery, even in space.

As the distance increases, such as missions to Mars and establishing colonies there, the difficulty of performing surgery will rise. Communication delays from Mars to Earth are about 20 minutes, which can be critical for life-or-death situations. Dr. Michael Barrett, an astronaut and physician, acknowledges that there are significant limitations on what doctors can do in space to save a critically ill or injured patient. The further one is from Earth, the more challenging the situation becomes. For example, if you are on the Moon, you can send an immediate distress signal, but returning to Earth may take five days—a challenging period for any patient needing urgent care.

Therefore, performing surgery in space is currently very difficult, if not impossible. In the event of a severe case or death of an astronaut, and with the difficulty of returning to Earth, the remaining crew would have to seriously consider how to handle the body—either by burying it in space within a pressure chamber and sending it out into the void or preserving it in some manner until they return to Earth.