By the early 20th century, aviation technology had advanced significantly, particularly in passenger transport. The Hindenburg airship was one of the most prominent modes of transatlantic travel, transporting thousands of passengers between Europe and the United States for nearly thirty years. However, this era came to a tragic end after the airship’s sixty-third voyage, which ended in disaster in May 1937. The Hindenburg caught fire while attempting to land in Lakehurst, New Jersey, killing 13 passengers, 22 crew members, and one ground worker. This disaster marked the end of the era of airship travel, as public confidence in this mode of transport was shattered, leading to a preference for airplanes.

The Hindenburg was in its second year of commercial service and was renowned for its unmatched luxury. It offered a travel experience that no other mode of transport could rival, cutting travel time across the Atlantic in half compared to ships. Designer Hugo Eckener initially wanted to use helium, a safer, less flammable gas than hydrogen, but the U.S. controlled most of the world’s helium supply and restricted its export due to military concerns. As a result, helium was difficult to obtain.

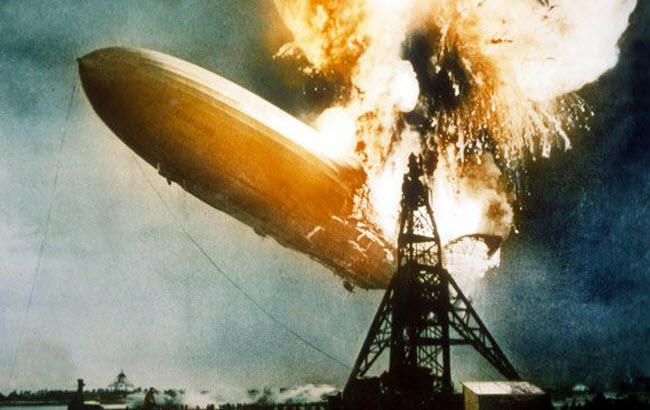

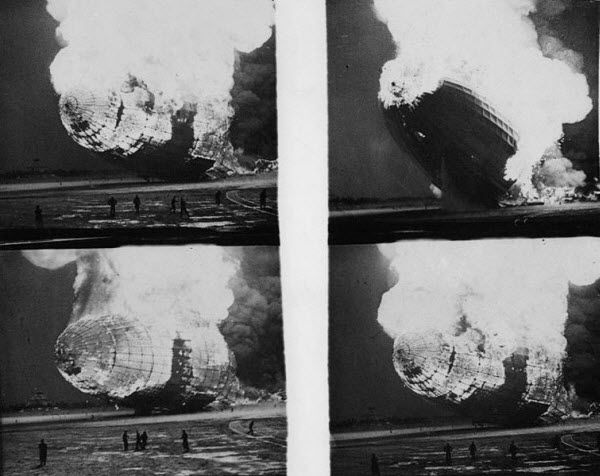

On the fateful journey, the airship departed from Frankfurt, Germany, on the evening of May 3, 1937. Despite the availability of faster airplanes, passengers preferred the Hindenburg for its opulence and comfort. The airship carried 36 passengers instead of its full capacity of 70 due to an unusually large crew of 61, including 21 trainees. Everything proceeded as planned, with the return journey fully booked by passengers who were mostly attending Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation. Upon reaching the United States on May 6, thunderstorms at the landing site in Lakehurst, New Jersey, prevented an immediate landing. Captain Max Pruss took the airship on a scenic tour over Manhattan, New York, drawing crowds who rushed outside to see it. At 7:00 p.m., he began preparations to land. By 7:11 p.m., he reduced speed, and at 7:21 p.m., while at an altitude of 90 meters, he began releasing landing lines and mooring cables for the ground crew to secure the airship. At 7:25 p.m., witnesses reported seeing part of the airship’s outer fabric fluttering, indicating a gas leak and blue flames, possibly due to static electricity. This led to a muffled explosion, followed by a massive fire.

As the fire engulfed the airship and it began its descent, a group of reporters was on the ground awaiting its arrival, including radio journalist Herbert Morrison and sound engineer Charlie Nelson. Morrison’s account of the disaster became legendary, though it was recorded and broadcast the following day rather than being a live transmission. His dramatic report included:

“It’s practically still up there… They’ve dropped the lines from the airship, and a number of men on the ground have taken them, and the rain has started again… The rain has slowed down a little… It’s on fire! Get this, Charlie… It’s fire… It’s crashing terribly… Oh God… Please get out of the way… It’s burning and on fire… It’s crashing into the mooring mast and all the people are in it… This is awful… This is one of the worst disasters in the world… Flames are shooting up to the sky, ladies and gentlemen… There’s smoke, and there are flames… Now… the frame is crashing to the ground, and all the passengers are screaming here… I can’t even talk to people… I can’t talk… Everyone is gasping for air… I’m sorry… I can hardly breathe… This is awful… Guys, I’m going to have to stop for a minute because I’ve lost my voice. This is the worst thing I’ve ever seen.”

Inside the airship, several survivors jumped from windows and ran to escape the fire. Among them was Werner Franz, a 14-year-old crew member who survived by jumping from a supply hatch and landing on the ground, free of debris. He lived until 2014, at the age of 92, and was considered the last surviving crew member.

Following the disaster, investigations were conducted to determine the cause. Although a definitive conclusion was not reached, most believe the fire was ignited by static electricity that sparked the hydrogen gas. Regardless of the exact cause, the incident destroyed public confidence in airships and marked the end of their era. Airplane travel soon replaced transatlantic airship travel, and a memorial now stands at the crash site to honor the victims of the disaster.

Quick Facts About the Hindenburg

- It Had a Smoking Room: The Hindenburg featured luxurious amenities, including a smoking room located below the storage compartment filled with seven million cubic feet of flammable hydrogen gas. Passengers could purchase cigarettes, including Cuban cigars, in this room. Given that hydrogen is lighter and rises, its presence in the smoking room was minimal. The room was designed to prevent hydrogen from entering, and a guard ensured all smoking materials were extinguished before passengers left.

- It Had a Lightweight Piano Made for the Airship: The Zeppelin company, owner of the Hindenburg, contracted a piano manufacturer to create a lightweight piano specifically for the airship. Weighing 180 kilograms, it was used during the airship’s first year of service. Fortunately, it was not aboard during the tragic accident.

- Mail Survived the Crash and Was Delivered: The airship carried approximately seventeen thousand letters and packages on its final voyage. Despite the disaster and massive fire, over 150 pieces of mail, preserved in a protective box, survived. They were stamped four days later and delivered to their recipients, later fetching high prices due to their association with the disaster.

- Goebbels Wanted to Rename It After Hitler: Due to the airship’s grandeur, Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels wanted to rename it after Nazi leader Adolf Hitler. However, designer Hugo Eckener, who was not a supporter of the Nazis, refused and named it after the late German President Paul von Hindenburg. Hitler was reportedly pleased that the airship, which ended in disaster, did not bear his name.

- Despite Its Infamy, It Was the Third Deadliest Incident: While the Hindenburg disaster is the most famous, there were previous incidents with higher fatality rates. On April 4, 1933, the U.S. Navy airship Akron crashed off the coast of New Jersey during a storm, killing all 76 aboard except three. On October 5, 1930, a British Army airship crashed in France, resulting in 48 deaths out of 54 passengers, including Air Minister Lord Thompson, the founder of the British airship program, and many of the ship’s designers.