Football, known as soccer in some countries, is the world’s most popular and widely played sport. It holds the record for the largest number of players and fans globally. The game’s simplicity contributes to its widespread appeal—its basic rules are easy to understand, and it requires minimal equipment. Football can be played almost anywhere: on official fields, in sports halls, on school playgrounds, and even in streets, parks, and beaches. Consequently, it’s no surprise that you find players from all walks of life engaging in the sport. Football is also thrilling, filled with excitement, skills, and tactics that captivate audiences. The sport has seen significant growth, with FIFA estimating that by the early 21st century, there would be approximately 250 million football players, both amateur and professional, and over 1.3 billion fans. A 2010 statistic revealed that the cumulative viewership of World Cup matches, the premier tournament in football, had surpassed 26 billion viewers—a staggering figure that has led major global corporations to sponsor the sport and its tournaments, yielding substantial profits.

The History of Football

Modern football originated in Britain during the 19th century. Prior to the Middle Ages, various forms of football were played in towns and villages with local customs and minimal rules. The Industrial Revolution reduced people’s leisure time, diminishing interest in the sport and leading to legal restrictions against the violent and destructive aspects of traditional football. Despite this, football was practiced as a winter sport in public schoolhouses like Winchester, Charterhouse, and Eton, each with its own set of rules. The differences in these rules made it difficult for students to play together once they moved on to universities. Consequently, in 1843, efforts began to standardize the rules, culminating in the “Cambridge Rules” of 1848, adopted by many public school students and spread by alumni who formed football clubs. By 1863, a series of meetings among clubs in London and surrounding areas led to the establishment of standardized rules, including a ban on carrying the ball, although goalkeepers were exempted from this restriction in 1870.

However, the new rules faced resistance in Britain, with many clubs, especially in Sheffield, retaining their own rules. Sheffield, the home of the first regional club to join the Football Association, established the Sheffield Football Association in 1867, a pioneer for future county associations. Matches between Sheffield and London clubs in 1866, and a subsequent match between teams from Middlesex and Kent in 1867, were played under revised rules. By 1871, fifteen clubs accepted an invitation to participate in a competition and contributed to purchasing a trophy. By 1877, British football associations agreed on a unified law, with 43 clubs competing.

Professionalism in Football

The development of modern football was closely linked to industrialization and urbanization in Victorian Britain. The working-class population in industrial towns and cities gradually lost interest in rural pastimes and sought new forms of collective entertainment. By the mid-19th century, factory workers turned to football on Saturday afternoons, and urban institutions like churches, trade unions, and boys’ schools formed recreational teams. Increased literacy among adults led to more media coverage of the sport, while transportation systems like railways and trams allowed players and spectators to travel to matches. Average attendances in England rose from 4,600 in 1888 to 7,900 in 1895, 13,200 in 1905, and 23,100 by the outbreak of World War I. Football’s popularity reduced public interest in other sports, notably cricket.

As the sport spread, leading clubs, especially those in Lancashire, began charging spectators as early as the 1870s. Despite the Football Association’s amateurism rules that allowed illegal payments to attract skilled working-class players, often from Scotland, players and Northern England clubs sought a professional system to compensate for lost wages and injury risks. The FA’s strong opposition aimed to maintain amateurism and shield the sport from upper-middle-class influence.

The professionalism issue reached a crisis in England in 1884 when the FA expelled two clubs for using professional players. However, paying players became common, leaving the FA with limited options. With working-class players gaining influence, upper-class individuals turned to other sports like cricket and rugby. Professionalism also led to further modernization of the sport, including the establishment of the Football League in 1888, which allowed ten leading northern and midland teams to compete systematically. The Second Division was introduced in 1893, increasing the total number of teams to 28. Irish and Scottish associations were formed in 1890, the Southern League started in 1894, and while it was absorbed by the Football Association in 1920, professional football did not become a major profit-making enterprise. Clubs were limited companies focused on securing grounds and gradually improving stadium facilities. Businessmen owned and managed most English clubs, but shareholder profits were minimal, with the main reward being the enhancement of local club status.

Subsequent national leagues abroad followed the British model, including league championships and at least one annual cup competition, with a promotion and relegation hierarchy. The Netherlands established its league in 1889, but professionalism only arrived in 1954. Germany held its first national championship season in 1903, with the fully professional German Bundesliga emerging after 60 years. In France, where football was introduced in the 1870s, the professional league did not start until 1932, following the adoption of professionalism in South American countries like Argentina and Brazil.

The Global Organization

By the early 20th century, football had spread throughout Europe but needed international organization. The solution came in 1904 when representatives from football associations in Belgium, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland founded FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association). Despite Englishman Daniel Burley Woolfall being elected president in 1906, and the original nations (England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales) joining by 1911, the British associations mocked the new body, forcing FIFA members to submit to British control of the game’s rules through the International Board created by the original nations in 1882. However, in 1920, the British associations withdrew from FIFA after failing to convince other members to expel Germany, Austria, and Hungary following World War I. The British associations rejoined FIFA in 1924 but soon insisted on a strict definition of amateurism, particularly for Olympic football, which other nations did not follow. The British withdrew again in 1928 and remained outside FIFA until 1946. During this period, FIFA established the World Cup, which the British remained indifferent to, and their national teams were not invited to the first three tournaments (1930, 1934, and 1938). For the 1950 tournament, FIFA decided that the top two British Home Nations teams would qualify, with England winning but Scotland (the second-place team) choosing not to compete.

Despite occasional international tensions, football’s popularity continued to rise. It made its Olympic debut in London in 1908 and has been included in every Summer Games since (except for Los Angeles 1932). FIFA also grew steadily, especially in the latter half of the 20th century, strengthening its position as the global governing body of the sport. Guinea became FIFA’s 100th member in 1961, and by the early 21st century, more than 200 countries were registered members, exceeding the number of UN member states.

While the World Cup is the foremost football tournament, FIFA has overseen other significant competitions. Youth tournaments began in 1977 and 1985, leading to the creation of the World Youth Championship (for players aged 20 and under) and the U-17 World Cup. The Futsal World Cup started in 1989, followed by the first Women’s World Cup in China in 1991. FIFA introduced the Olympic football tournament for players under 23 years old and held the first women’s Olympic football tournament four years later. The Club World Cup began in Brazil in 2000, and the U-19 Women’s World Cup started in 2002.

FIFA membership is open to all national associations under certain conditions, including accepting FIFA’s authority and possessing adequate football infrastructure (facilities and internal organization). FIFA laws require members to be affiliated with continental associations, the first of which was CONMEBOL (South American Football Confederation) in 1916. UEFA (European Football Association) and AFC (Asian Football Confederation) were formed in 1954, followed by CAF (African Football Confederation) in 1957, CONCACAF (Confederation of North, Central America, and Caribbean Association Football) in 1961, and OFC (Oceania Football Confederation) in 1966. These associations organize continental and club competitions, elect representatives to FIFA’s executive committee, and promote football within their regions. In turn, all football players, agents, tournaments, national associations, and continental federations must recognize the authority of FIFA’s Court of Arbitration for Sport, which acts as a supreme court for football disputes.

Until the early 1970s, FIFA’s control—and thus global football—was dominated by Northern Europeans, under Englishmen Arthur Drewry (1955-1961) and Stanley Rous (1961-1974). FIFA maintained a somewhat conservative aristocratic relationship with national and continental bodies and did little to promote football in developing countries or explore the sport’s commercial potential during the post-war economic boom in the West. FIFA’s leadership was more concerned with organizational issues like confirming amateur status in Olympic competitions or banning illegal player transfers. For instance, the memberships of Colombia (1951–54) and Australia (1960–63) were temporarily suspended by FIFA after clubs in these countries signed players who had broken contracts elsewhere.

Over time, increasing African and Asian membership within FIFA undermined European control. In 1974, Brazilian João Havelange was elected president with broad support from Latin American countries. He sought to increase the number of teams in the World Cup and introduced more substantial marketing deals and television rights to increase revenues. FIFA’s most ambitious project was the development of a global marketing and television empire, spearheaded by Havelange’s successor, Sepp Blatter, who led FIFA from 1998 to 2015. This era witnessed the expansion of the World Cup and the Women’s World Cup, as well as increased sponsorship and broadcasting deals. Blatter’s presidency, despite being plagued by corruption scandals, marked a period of tremendous growth for FIFA’s global influence and revenue.

Hooliganism in Football

The global spread of football has brought together people from diverse cultures to celebrate a shared passion for the game. However, this enthusiasm has also given rise to a worldwide epidemic of football hooliganism, sometimes escalating into violence both inside and outside stadiums. Concerns about fan violence and hooliganism began to emerge in the 1960s, with early focus on British supporters. In response, measures were implemented to combat such behavior, including architectural improvements to stadiums worldwide. In Latin America, stadiums were built with trenches and high fences, and many venues in Europe now prohibit alcohol and have eliminated standing areas for fans.

Historically, some of the earliest modern hooligan groups were found in Scotland, where sectarian rivalries existed between supporters of Glasgow Rangers, mostly Protestant unionists, and Celtic, predominantly associated with the Irish Catholic community. During the interwar years, these groups clashed in the streets whenever the teams met. However, since the late 1960s, English football hooliganism gained notoriety, especially when following teams abroad. The peak of fan violence occurred in the mid-1980s during the European Cup final in 1985 between Liverpool and Juventus at the Heysel Stadium in Brussels. The tragedy resulted in the deaths of 39 fans (38 Italians and one Belgian) and injuries to over 400 when Liverpool supporters charged at rival fans, causing a stadium wall to collapse. In response, English clubs were banned from European competition until 1990. By then, hooliganism had become entrenched in many other European countries, and by the early 21st century, hooligans in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and other nations were also prominent. Among the most notorious were Italy’s “Ultras,” France’s “Hooligans,” and Spain and Latin America’s “Hinchadas.” Argentina perhaps saw the worst consequences, with approximately 148 deaths between 1939 and 2003 in violent incidents often involving security forces.

The causes of football hooliganism are diverse and context-dependent. High levels of alcohol consumption can exacerbate fan aggression, but this is not the sole factor. Hooliganism often takes on a cultural dimension. In major tournaments, hooligans may spend weeks targeting rival supporters. Research in Britain indicates that these groups do not usually come from the poorest segments of society but rather from relatively affluent working-class backgrounds. In Southern Europe, especially Italy, spectator violence can stem from cultural rivalries and deep-seated tensions between neighboring cities or between the North and South. In Latin America, fan violence is often linked to recent political history, such as dictatorship and repressive state methods of social control. In Argentina, the rise in violence from the late 1990s has been attributed to the severe economic and political downturn.

In some cases, football hooliganism has forced politicians and the judiciary to intervene directly. In England, the Conservative government in the 1980s targeted football hooligans with legislation, and subsequent administrations introduced further measures to control spectator behavior. These included creating family-only stands to attract wealthier viewers. Critics argued that these policies also diminished the excitement of matches and stadiums. In Argentina, courts briefly suspended football matches in 1999 to curb violence, acknowledging that fan violence poses a significant barrier to the economic and social health of the sport. The tragedies, such as the 2001 disaster in Ghana that killed 126 people, and incidents in Peru in 1964 and Zimbabwe in 2000, where inadequate crowd control measures led to significant loss of life, highlight the serious consequences of mismanaged events. Despite these issues, it would be a mistake to portray the vast majority of football fans as inherently violent or xenophobic. Since the 1980s, fan groups, in collaboration with football organizers and players, have launched local and international campaigns against racism and, to a lesser extent, sexism. International football bodies have also awarded prizes for good conduct among fans at major tournaments.

The Laws of Football

The rules of football, concerning the requirements and field of play, participant behavior, and result determination, are set out in a set of laws approved by the International Football Association Board (IFAB), comprising representatives from FIFA and the four UK football associations authorized to amend the laws.

Equipment and Field

The objective of football is to maneuver the ball into the opponent’s goal using any part of the body except the hands and arms. The team that scores the most goals wins. The ball is round, covered in leather or other suitable material, inflated, and must have a circumference between 68-70 cm and a weight between 410-450 grams. The game lasts 90 minutes, divided into two halves of 45 minutes each, with additional time added by the referee for stoppages (e.g., player injuries). If the score is tied and a winner must be determined, extra time is played, followed by a penalty shootout if necessary.

The penalty area, a rectangular zone in front of the goal, measures 40.2 meters by 16.5 meters into the field. The goal frame, supported by a net, is 7.3 meters wide and 2.4 meters high. The pitch dimensions are 90 to 120 meters in length and 45 to 90 meters in width, with international matches requiring dimensions of 100.5-109.7 meters in length and 64-73.1 meters in width. Women and children may play on smaller pitches. The game is controlled by a referee, who is also the timekeeper, with two assistants patrolling the touchlines and indicating when the ball goes out of play or when players are offside. Players wear numbered shirts, shorts, and socks to identify their team, and must also wear appropriate footwear and shin guards. Both teams must wear distinguishable kits, and goalkeepers must be easily identifiable from all other players and referees.

Fouls

Free kicks are awarded for fouls or rule violations. When taking a free kick, all opposing players must be at least 9 meters away from the ball. Free kicks can be direct (from which a goal can be scored directly) if the foul is serious, or indirect (from which a goal cannot be scored directly) if the foul is less severe. Penalty kicks, introduced in 1891, are awarded for more serious fouls committed within the penalty area. These are direct free kicks taken from a spot 11 meters from the goal, with all players except the goalkeeper being outside the penalty area. Since 1970, players committing serious offenses are shown a yellow card as a warning, with a second yellow resulting in a red card and dismissal from the game. Direct red cards are also given for severe offenses like violent conduct.

Rules

There have been few major changes to the rules of football over the 20th century. The most significant rule change came in 1925 with the revision of the offside rule. Previously, an attacking player was offside if fewer than three opposing players were between them and the goal when the ball was played to them. The rule was adjusted to require only two opposing players, effectively increasing scoring opportunities.

Recent rule changes have increased the pace of attacking play and the amount of active play in matches. The back-pass rule now prevents goalkeepers from handling the ball after it has been deliberately kicked to them by a teammate. Players who deliberately commit fouls to prevent opponents from scoring are penalized with red cards. Diving (pretending to be fouled) to win free kicks or penalties is also penalized. Time-wasting is addressed by requiring goalkeepers to release the ball within six seconds and by removing injured players with stretchers.

The interpretation of football rules can vary by cultural context. For example, a high foot may not be deemed dangerous play in Britain as it might be in Southern Europe. Similarly, British games might be more lenient on tackles from behind compared to recent World Cup matches. FIFA insists that the referee’s decision is final, but video evidence is now used by disciplinary committees to review violent play or assess referees’ performance, and video is also used during matches to review certain plays.

Football Tactics and Strategies

Using the feet and legs to control and pass the ball are the simplest skills in football. Heading the ball is particularly notable when receiving long aerial passes. Since the game’s inception, players have showcased individual skills through dribbling past opponents. However, football is fundamentally a team sport that relies on passing among team members. The basic playing styles and skills reflect players’ positions on the field. Goalkeepers need agility and height to reach and prevent shots on goal. Defenders challenge direct attacking play and are tasked with clearing the ball from attackers’ heads and feet. Midfielders operate across the pitch, often possessing a mix of attributes such as good tackling, speed, and creating scoring opportunities through precise passing. Wingers tend to have good speed and dribbling skills and are able to deliver crosses into the opponent’s penalty area, providing scoring opportunities for forwards. Forwards are often strong shooters, capable of penetrating defenses and proficient at scoring from various angles.

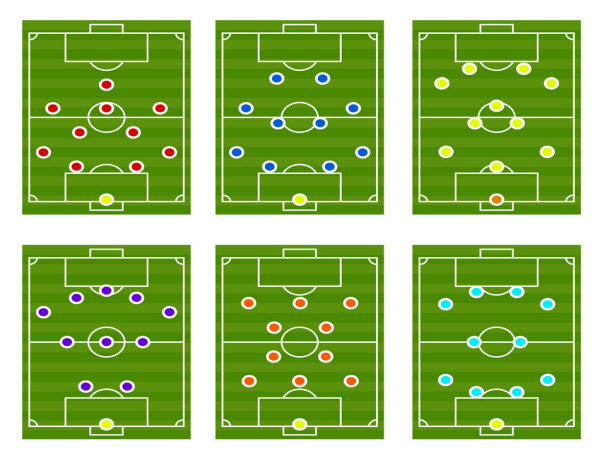

Tactics are crucial in game planning and are responsible for linking team formations with playing styles, such as attacking, counter-attacking, slow or fast pace, short or long passing, or team versus individual play. The goalkeeper is not included in the formation, and players are arranged by position, with defenders listed first, followed by midfielders, and then forwards (e.g., 4-4-2 or 2-3-5). Historically, teams played attacking formations (such as 1-1-8 or 1-2-7) with a strong emphasis on individual dribbling skills. In the late 19th century, the Scottish introduced passing play, and Preston North End developed the more cautious 2-3-5 system. Although English football was associated with kicking and rushing, teamwork and deliberate passing were clearly more forward-looking aspects of effective play.

Between the wars, Herbert Chapman, the innovative manager of Arsenal in London, created the WM formation with five defenders and five forwards. While some teams outside Britain used this tactic, others (like Italy in the 1934 World Cup and many South American teams) retained the original 2-3-5 formation. With the outbreak of World War II, many clubs and regions developed distinctive playing styles, such as combative play and short-passing skills from the Danube School, Creole artistry, and Argentine dribbling.

Post-war, various tactical innovations emerged. Hungary introduced the false nine to confuse defenders about whether to mark a midfielder or allow them to roam freely behind forwards. The Swiss “lock” system, perfected by Karl Rappan, involved players swapping positions and roles depending on the game’s flow. Italian clubs, notably Inter Milan, adopted attacking football, and the “Catenaccio” system, developed by Helenio Herrera, adapted the lock system with a sweeper (libero) in defense. While effective, this system often led to defensive, sometimes dull football.

Several factors contributed to defensive and negative playing styles. Rules in football competitions (such as European club tournaments) sometimes encouraged visiting teams to play for a draw, while home teams were very cautious about conceding goals. Local and national pressures to avoid losing matches were intense, and many coaches discouraged players from taking attacking risks. On the international stage, Brazil became the greatest symbol of individual football skill, adopting the 4-2-4 formation from Uruguay to win the 1958 World Cup. This formation was widely broadcast on television, showcasing highly skilled players to a global audience. In the early 1970s, the Dutch “Total Football” system, with players performing both defensive and attacking duties, was exemplified by Johan Cruyff. Ajax Amsterdam played a significant role in promoting Total Football through the 3-4-3 formation.