The Himalayas are a major mountain range located in Asia, separating the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. This vast mountain system includes the Himalayas, Karakoram, and Hindu Kush ranges, stretching across six countries: Bhutan, China, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. The range is the source of three of the world’s most significant river systems: the Indus, the Ganges-Brahmaputra, and the Yangtze, supporting an estimated 750 million people within these river basins. The name “Himalaya” is derived from the Sanskrit term meaning “abode of snow,” reflecting the perpetual snow capping the peaks. It is also the highest mountain range on Earth, often referred to culturally as the “Roof of the World” due to its towering peaks that exceed 8,000 meters above sea level. The most notable of these peaks is Mount Everest, which attracts climbers from around the globe in their quest to reach its summit.

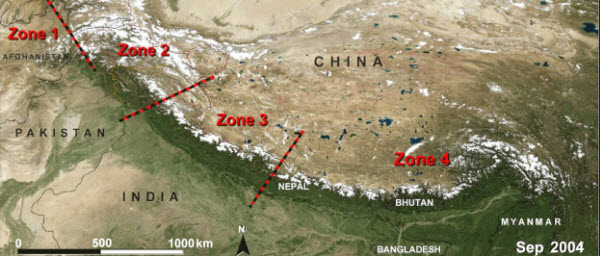

The Himalayas contain over 100 separate peaks exceeding 7,200 meters in height, making it one of the most rugged mountain barriers globally. The range forms an arc stretching approximately 2,400 kilometers, varying in width from 400 kilometers in Kashmir to 150 kilometers in Arunachal Pradesh. The eastern half of the range is notably higher than the western half, and it is composed of three parallel bands running longitudinally, separated by various valleys. For thousands of years, due to its immense size and expanse, the Himalayas have served as a natural barrier to human movement, particularly preventing interaction between the people of the Indian subcontinent and those from China and Mongolia. This isolation has led to significant linguistic and cultural differences between these regions and has also hindered trade routes and military campaigns across its expanse. For instance, Genghis Khan was unable to extend his empire southward into the Indian subcontinent due to the Himalayas.

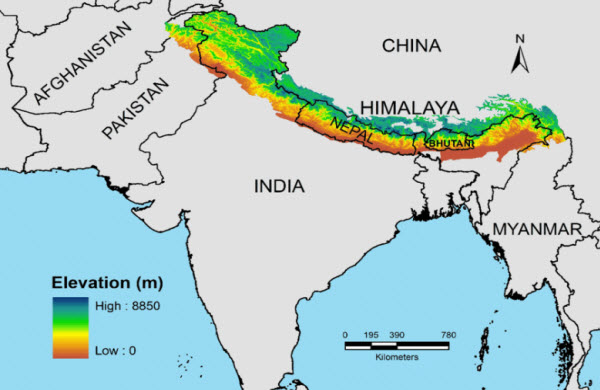

The Himalayas boast the highest peaks in the world, with Mount Everest at the border of Nepal and Tibet in China being the tallest at 8,850 meters. It is followed by K2, located on the border between northern Pakistan-administered areas and China’s Xinjiang region, which stands at 8,611 meters and is considered one of the most challenging mountains to climb. The third highest peak is Kangchenjunga, straddling the India-Nepal border, with an elevation of 8,586 meters.

Some regions of the Himalayas are closely associated with religions, particularly Buddhism and Hinduism, where the mountains are personified as the deity “Himalaya,” father-in-law to the god Shiva. There are numerous Tibetan Buddhist sites and temples, including the residence of the Dalai Lama, and it is also considered the location of the legendary city of Shambhala, which some believe to be real, while others consider it a purely spiritual concept. Additionally, it is believed that the Himalayas harbor the mythical Yeti, described as a large, ape-like creature.

Himalayan Environment

The flora and fauna of the Himalayas vary with climate, rainfall, altitude, and soil conditions. The climate ranges from tropical at the base of the mountains to perennial ice and snow at the highest elevations. Annual precipitation increases from west to east along the range, resulting in diverse plant and animal communities. The Himalayas are divided into several distinct zones:

Lowland Forests – Found in the Gangetic plain at the base of the mountains, this sedimentary plain depends on the Indus and Ganges-Brahmaputra river systems. Vegetation varies from west to east with rainfall, including thorn forests in northwest Pakistan and Punjab, to moist deciduous forests in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal. The Brahmaputra valley features semi-evergreen forests in Assam.

Terai Belt – Situated above the Gangetic plain, the Terai is a seasonal swampy area with sandy and clayey soil. It receives continuous rainfall, with rivers from the Himalayas slowing and spreading across the flat Terai region, depositing fertile silt during the monsoon and receding in the dry season. This belt includes a mosaic of grasslands, savannas, and deciduous forests.

Bhabhar Belt – Above the Terai, the Bhabhar is an elevated area with porous, rocky soil consisting of debris washed down from higher ranges. It has a subtropical climate and is home to subtropical pine forests in the west and broad-leaved subtropical forests in the central part.

Siwalik Hills – Also known as the Shivalik Hills, this outer, discontinuous range stretches across Pakistan, India, Nepal, and Bhutan. Peaks generally range from 600 to 1,200 meters in height. The southern slopes are steeper along a major fault line, while the northern slopes are less steep, allowing rainwater to seep into the Bhabhar and Terai.

Inner Terai Valleys – Open valleys located north of the Siwalik Hills, such as Dehradun in India and Chitwan in Nepal.

Mahabharat Range – Prominent ranges with elevations between 2,000 to 3,000 meters, formed along a major fault zone with steep southern faces and gentler northern slopes. They are connected except for river gorges that cut through the range.

Midlands – A mountainous area with an average elevation of around 1,000 meters directly north of the Mahabharat Range, extending over 100 kilometers.

Alpine Shrubs and Meadows – Above the tree line, alpine shrubs and meadows cover the northwestern, eastern, and western Himalayas, leading to tundra in the highest ranges.

Formation and Growth of the Himalayas

The Himalayas are among the youngest mountain ranges on Earth. According to modern plate tectonic theory, their formation resulted from a continental collision along the convergent boundary between the Indian-Australian Plate and the Eurasian Plate. This collision is believed to have started in the Late Cretaceous, around 70 million years ago. As the northward-moving Indian-Australian Plate collided with the Eurasian Plate, the Tethys Ocean, once identified by stable oceanic sediments and volcanoes, was entirely closed. Instead of sinking, these sediments formed mountain chains. The Indian-Australian Plate continues to move horizontally beneath the Tibetan Plateau, causing uplift, which also led to the formation of the Arakan Yoma ranges in Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal.

The Indian-Australian Plate still moves at a rate of 67 millimeters per year, and over the next ten million years, it will traverse 1,500 kilometers across Asia. Approximately 20 millimeters per year of the convergence between India and Asia are absorbed by the push along the southern front of the Himalayas, causing them to rise about 5 millimeters annually, making them geologically active. This ongoing movement results in significant seismic activity, with occasional earthquakes.

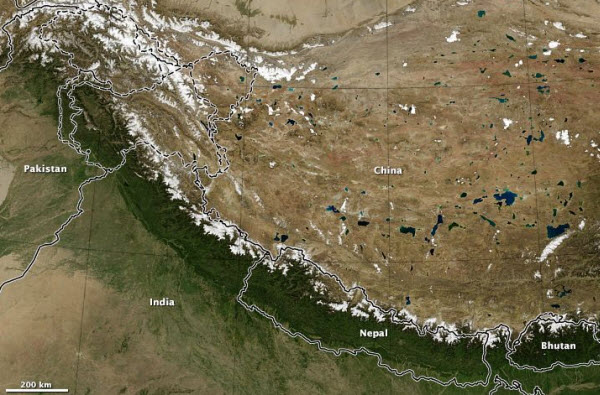

Glaciers, River Systems, and Lakes

The Himalayan range contains a large number of glaciers, including the Siachen Glacier, the largest outside the polar regions, along with other notable glaciers such as Gangotri, Yamunotri, Nubra, Biafo, Baltoro (Karakoram region), Zemu, and the Khumbu Glaciers (Everest region).

The upper regions of the Himalayas remain snow-covered year-round despite their proximity to the tropics. These areas are sources for many major rivers that converge into two primary river basins:

Western Rivers – These rivers drain into the Indus Basin, with the Indus River being the largest. Originating in Tibet from the confluence of the Sengge and Gar rivers, it flows southwest through Pakistan into the Arabian Sea, fed by the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej rivers.

Ganges-Brahmaputra Basin – The major rivers in this basin are the Ganges and Brahmaputra. The Ganges originates from the Gangotri Glacier, flowing southeast through northern India’s plains, fed by the Kanananda, Yamuna, and other tributaries. The Brahmaputra, initially called the Tsangpo in western Tibet, flows east through Tibet and west through Assam’s plains, where it joins the Ganges in Bangladesh and empties into the Bay of Bengal through the world’s largest river delta.

Eastern Rivers – Rivers in the far eastern Himalayas feed the Irrawaddy River, which originates in eastern Tibet and flows south through Myanmar into the Andaman Sea. The Salween, Mekong, Yangtze, and Huang He (Yellow River) also originate from parts of the Tibetan Plateau and are not considered true Himalayan rivers. Recently, scientists have observed a significant increase in the rate of glacier retreat across the region due to global warming and climate change. Though the full impact may take years to understand, this could spell disaster for the hundreds of thousands who depend on glaciers to feed northern India’s rivers during dry seasons.

In addition to rivers, the Himalayas are home to numerous lakes, most of which are located below 5,000 meters in elevation. The largest of these is Pangong Tso, straddling the border between India and Tibet, at an elevation of 4,600 meters, with a width of 8 kilometers and a length of about 134 kilometers. Other notable high-altitude lakes include the Gurudongmar Lake in northern Sikkim, at 5,148 meters, and the Tsongmo Lake near the India-China border, along with the Tsho Rolpa Lake in a region that was previously closed to outsiders.

Impact on Climate

The Himalayas have a profound impact on the climate of the Indian subcontinent and the Tibetan Plateau by blocking the cold, dry winds from the Arctic from moving southward, making South Asia warmer

and wetter. This has resulted in the monsoon climate pattern, characterized by a seasonal reversal of winds and heavy rainfall during the monsoon season, which is crucial for agriculture in the region.

The range also affects global weather patterns. Its height influences the Indian Ocean monsoon, while its proximity to the Tibetan Plateau impacts global atmospheric circulation. The Himalayas play a role in the winter monsoon over Asia, and their height contributes to a significant temperature difference between the land and ocean, affecting regional weather.

Overall, the Himalayas are not only a significant geographical feature but also a crucial component of the global climate system, with ongoing research exploring their complex interactions with global weather and climate patterns.