The Indian Ocean is the third-largest oceanic division on Earth, following the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Covering approximately 20% of the Earth’s water surface, it spans an area of about 73.6 million square kilometers, including the Red Sea and the Arabian Gulf. Bordered to the north by Asia, including the Indian subcontinent from which it derives its name, the Indian Ocean meets the Southern Ocean near Antarctica in the south. To the west, it is flanked by Africa, while to the east, it is bordered by the Malay Peninsula, the Sunda Islands, and Australia. The ocean’s boundaries are delineated from the Atlantic Ocean by the 20th meridian east and from the Pacific Ocean by the 147th meridian east. The Indian Ocean is vast, with a volume of 292.1 million cubic kilometers. It features several small islands along its continental margins, some of which are internationally recognized independent nations, such as Madagascar—the fourth-largest island in the world—along with Comoros, Seychelles, Maldives, Mauritius, and Sri Lanka. Strategically important as a transit route between Asia and Africa, the Indian Ocean has been the site of numerous international conflicts over control. Despite its vastness, no single nation has dominated it entirely, until the early 19th century when the United Kingdom acquired substantial territories around it. After World War II, countries like India and Australia also asserted their control.

Historical Context of the Indian Ocean

Early civilizations flourished in Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt, and the Indian subcontinent, centered around the Tigris, Euphrates, Nile, and Indus rivers, respectively. During Egypt’s Old Kingdom (around 3000 BCE), sailors ventured across the Indian Ocean to Punt, believed to be part of present-day Somalia, returning with gold and myrrh. The first known maritime trade occurred between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley around 2500 BCE.

The calm waters of the Indian Ocean facilitated early trade routes compared to the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Its strong monsoon winds allowed ships to sail westward easily early in the season, wait for several months, and then return east. This enabled Indonesian peoples to cross the Indian Ocean and settle in Madagascar. By the 2nd or 1st century BCE, the Greek navigator Eudoxus crossed the Indian Ocean, and it is said that Hippalus discovered the direct route from the Arabian Peninsula to India around this time. During the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, trade relations developed between Roman Egypt and the Tamil, Chola, and Pandya kingdoms in southern India.

From 1405 to 1433, Admiral Zheng He led large fleets from China’s Ming dynasty on voyages to the Indian Ocean, reaching the East African coast. In 1497, Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama navigated around the Cape of Good Hope and became the first European to sail to India. European ships, armed with heavy cannons, quickly dominated the trade in the region. Initially, Portugal attempted to establish dominance through fortifications in key straits and ports, but the small nation struggled to sustain such a large endeavor. By the mid-17th century, other European powers, such as the Dutch East India Company (1602-1798), emerged, and France and Britain established trading companies in the area. Eventually, the British became the primary power and, by 1815, had fully controlled the region.

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 rekindled European interest in the East, but no country succeeded in establishing commercial hegemony over it. After World War II, the United Kingdom withdrew, and India, the Soviet Union, and the United States partially replaced its influence. The latter two sought dominance during the Cold War by negotiating naval base locations. However, developing countries bordering the Indian Ocean strive to make it a “zone of peace” to ensure free shipping routes, even though the UK and the US maintain a military base on Diego Garcia Atoll in the central Indian Ocean.

Geography of the Indian Ocean

In 2000, the International Hydrographic Organization designated a fifth global ocean, which included the southern parts of the Indian Ocean extending from the Antarctic coast to the 60th parallel. Despite this, the Indian Ocean remains the third-largest of the world’s five oceans, containing major strategic chokepoints such as the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait, the Strait of Hormuz, the Malacca Strait, the southern entrance to the Suez Canal, and the Lombok Strait. It also includes several seas and gulfs, such as the Andaman Sea, the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal, the Great Australian Bight, the Gulf of Aden, the Gulf of Oman, the Lakshadweep Sea, the Mozambique Channel, and others.

Geology of the Indian Ocean

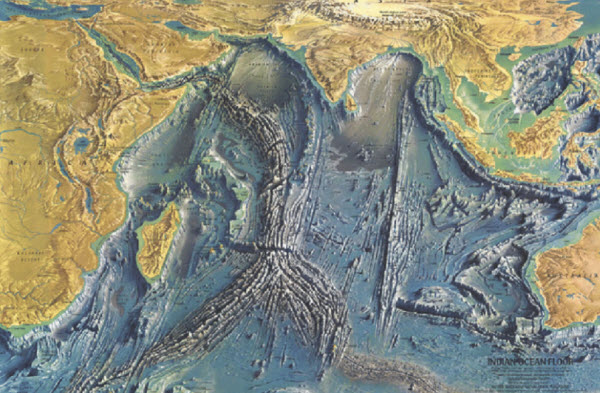

The Indian Ocean’s tectonic boundaries involve the convergence of the African, Indian, and Antarctic plates. The ocean floor features a central ridge system forming an inverted Y shape, with eastern, western, and southern basins divided into smaller troughs. The continental shelves of the Indian Ocean are narrow, averaging 200 kilometers wide, except for the western coast of Australia, where the shelf exceeds 1000 kilometers in width. The average depth of the ocean is 3890 meters, with the deepest point being the Diamantina Deep near the southwestern coast of Australia. Approximately 86% of its main basin is covered by marine sediments, with the remaining 14% covered by terrigenous sediments. Glacial drift predominates at the highest southern latitudes.

Characteristics of the Indian Ocean

Several major rivers flow into the Indian Ocean, including the Zambezi, the Arvandroud, the Sindhu, the Ganges, the Brahmaputra, and the Ayeyarwady. The monsoon winds primarily influence its currents, creating two major gyres: one in the Northern Hemisphere flowing clockwise and the other south of the equator moving counterclockwise. Deep water circulation is mainly controlled by inflows from the Atlantic Ocean, the Red Sea, and the Southern Ocean currents.

Salinity

Surface water salinity in the Indian Ocean ranges from 32 to 37 parts per thousand. The highest salinity is found in the Arabian Sea and in the belt between South Africa and southwestern Australia. Ice and icebergs are found year-round south of approximately 65 degrees south latitude.

Climate

Overall, the Indian Ocean is the warmest of the world’s oceans, with its northern part affected by the monsoon wind system. From October to April, strong northeastern winds prevail, while from May to October, southwesterly winds dominate. In the Arabian Sea, intense monsoon winds bring rains to the Indian subcontinent. In the Southern Hemisphere, the winds are generally milder, though summer storms near Mauritius can be severe. Changes in monsoon wind patterns sometimes result in cyclones impacting the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal.

Cold water upwelling in the eastern Indian Ocean is part of a climatic phenomenon known as the Indian Ocean Dipole, where the eastern part of the ocean becomes cooler than the western part.

Economic Significance of the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean provides major maritime routes linking the Middle East, Africa, and East Asia with Europe and the Americas. It experiences heavy traffic, especially for oil and petroleum products extracted from the Persian Gulf and Indonesia. Significant hydrocarbon reserves are exploited in the marine areas of Saudi Arabia, Iran, India, and western Australia, contributing about 40% of the world’s offshore oil production. Coastal countries, particularly India, South Africa, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Thailand, actively mine heavy mineral sands.

The warm waters of the Indian Ocean lead to reduced plankton production, making marine life relatively limited except in the northern extremities and a few scattered areas. Fishing fleets from Russia, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan focus on shrimp and tuna in the region.

Threats to the Indian Ocean

Global warming poses a significant threat to the coral reefs near the ocean’s surface, with the Indian Ocean containing 16% of the world’s coral reefs. Scientists documented that about 90% of shallow coral reefs, extending from 10 to 40 meters below the water’s surface, died in 1998 due to warm water temperatures. They anticipate worsening conditions due to projected global temperature increases of 2 to 2.5 degrees Celsius this century. Coral reef loss is a major concern as it jeopardizes marine life dependent on these ecosystems and diminishes natural wave barriers protecting coastlines from erosion.

Besides global warming, the Indian Ocean faces pollution threats from oil spills in the Arabian Sea, the Persian Gulf, and the Red Sea, which harm marine life. Endangered marine species in the region include manatees, seals, turtles, and whales.