Nelson Mandela was a South African political figure and human rights activist. Although he has passed away, he remains a historical icon for his country and a source of inspiration for many civil rights activists worldwide. He was the first black president of South Africa, serving for five years after dedicating most of his life to fighting and contributing to the anti-apartheid movement. He began this journey in his youth by joining the African National Congress (ANC) in 1942 and led his nation through peaceful and even military campaigns against the minority white government and its racist policies. Due to his human rights activities, Mandela spent 27 years in prison, the longest any political leader has been imprisoned in history. After his release, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993 for his previous struggle and subsequent efforts to dismantle the apartheid system in his country. Upon his presidency, he formed a multiracial government to oversee the transitional period. After retiring from politics in 1999, he remained a devoted advocate for peace and social justice, not only in his country but across the globe, until his death.

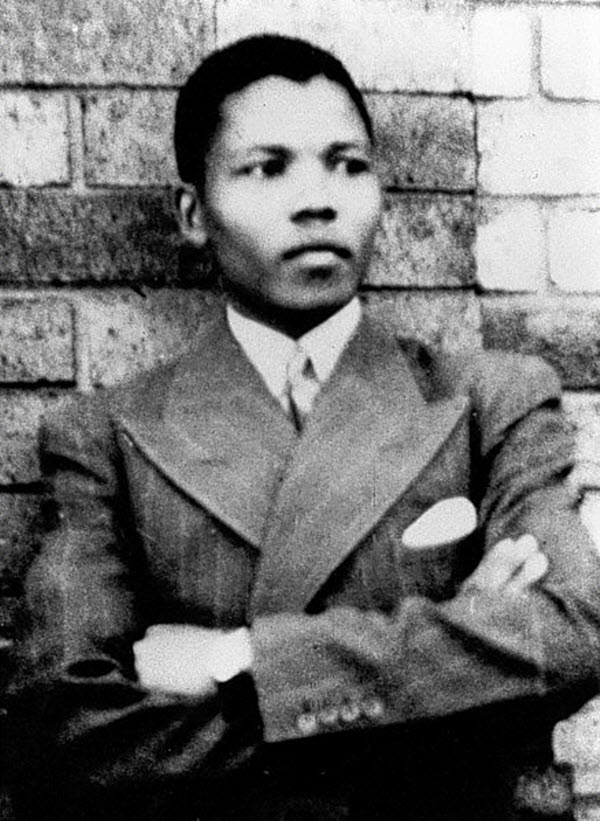

Early Life and Education

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born on July 18, 1918, in the small village of Mvezo on the banks of the Mbashe River in Transkei, South Africa. His Xhosa name, “Rolihlahla,” translates to “pulling the branch of a tree,” but is more commonly interpreted as “troublemaker.” Mandela’s father worked as an advisor to tribal chiefs but lost his title and wealth due to a dispute with the local colonial magistrate when Mandela was still an infant. Following this, his mother moved the family to Qunu, a smaller village north of Mvezo, in a narrow, grassy valley with no roads—only footpaths connecting pastures for livestock. The family lived in a hut, subsisting on locally grown maize, pumpkins, and beans, and drank from springs and streams. Mandela played with other children using toys made from natural materials like tree branches and clay.

Education and Political Awakening

Encouraged by a family friend, Mandela was baptized in the Methodist Church and became the first in his family to attend school. Influenced by the British education system in South Africa, his teacher gave him the new first name “Nelson.” At the age of 12, Mandela’s father passed away, a loss that dramatically altered his life. He was adopted by Chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo, who had been entrusted by Mandela’s late father to become his guardian. Mandela left his tranquil life in Qunu to move to the royal residence in Mqhekezweni, the capital of the Thembu Kingdom. Despite missing his previous village, he quickly adapted to the more developed surroundings.

While at Mqhekezweni, Mandela was given the same status and responsibilities as the chief’s other children and began his education in a single-room school next to the palace, studying English, history, and geography. During this time, his interest in African history grew, as he listened to stories from senior leaders about how Africans had lived relatively peacefully until the arrival of white colonizers, who took everything for themselves.

Political Awakening and University Life

At 16, Mandela participated in traditional Xhosa initiation rituals marking his transition into manhood. The ceremony was not just a surgical procedure but a meticulous rite of passage. African tradition held that an uncircumcised man could not inherit his father’s wealth, marry, or perform tribal rituals. Mandela participated with 25 other boys, embracing the customs of his people. However, his enthusiasm waned when the chief speaker, Mliangeli, lamented the subjugation of young black men, who were oppressed in their own land under white rule. Mandela later reflected that although the speaker’s words did not fully make sense to him at the time, they ignited his resolve to strive for an independent South Africa.

Mandela’s preparation for a prominent role came as he was educated at Wesleyan College, where he excelled academically and in athletics. Despite initial ridicule as a rural boy, he eventually made friends. In 1939, Mandela entered Fort Hare University, the only higher education institution for blacks in South Africa at the time, often compared to Harvard University for Africa. He focused on Roman-Dutch law, aiming to become a translator or clerk—one of the best professions available to black men at the time. During his second year, Mandela joined the student representative council and participated in a boycott and strike over food quality. This action led to his expulsion for the rest of the year, and his guardian was displeased, having already arranged for Mandela’s marriage and planned his future according to tribal customs.

Feeling trapped, Mandela fled to Johannesburg, working in various jobs, including as a guard and clerk, while pursuing a degree through correspondence courses. He later enrolled at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg to study law.

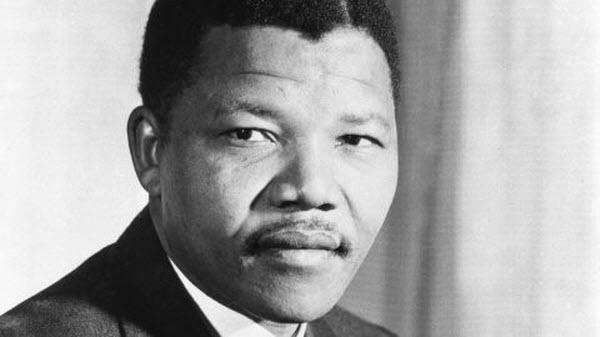

Anti-Apartheid Movement

Mandela quickly and actively engaged in the anti-apartheid movement, joining the African National Congress (ANC) in 1942. He became part of a group of enthusiastic youth within the ANC, known as the ANC Youth League, aiming to transform the party into a mass movement drawing strength from millions of disenfranchised farmers and workers. This group believed the party’s traditional petitioning methods were ineffective. In 1949, the ANC officially adopted the Youth League’s tactics of boycotts, strikes, civil disobedience, non-cooperation, and pursuing policy goals like full citizenship, land redistribution, labor rights, and compulsory education for all children.

For 20 years, Mandela led non-violent campaigns against the South African government’s racist policies, including the Defiance Campaign of 1952 and the Congress of the People in 1955. He co-founded the Mandela and Tambo law firm with Oliver Tambo, providing free or low-cost legal services to black individuals.

In 1956, Mandela and 150 others were arrested and charged with treason due to their political activities. They were later acquitted. As the ANC faced challenges from newer, more radical members who believed in more militant approaches, it lost much of its military support by 1959.

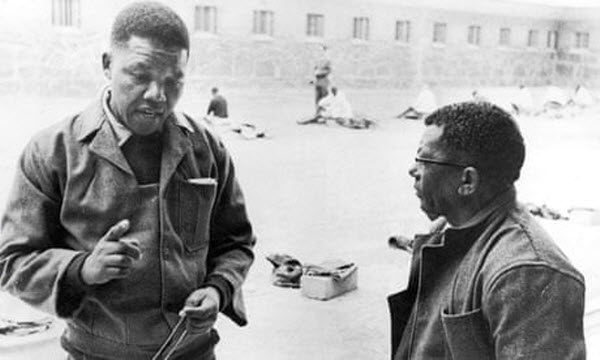

Imprisonment and Release

Mandela, once a proponent of peaceful protest, came to believe that armed struggle was the only way to achieve change. In 1961, he helped establish a militant branch of the ANC, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), dedicated to sabotage and guerrilla tactics against apartheid. That year, he also organized a national labor strike, for which he was arrested and sentenced to five years in prison. In 1963, Mandela and ten other ANC leaders were sentenced to life imprisonment for political crimes, including sabotage.

Mandela spent 27 years in prison, with 18 of those years on Robben Island. During his imprisonment, he contracted tuberculosis and received minimal medical care. Nevertheless, he earned a law degree through a correspondence course from the University of London. In 1981, South African intelligence agent Gordon Winter revealed a plot by the South African government to arrange Mandela’s escape and then kill him during recapture, but British intelligence thwarted the plan.

Mandela’s imprisonment became a symbol of resistance, prompting an international campaign for his release. In 1982, Mandela and other ANC leaders were transferred to Pollsmoor Prison to facilitate communication with the South African government. In 1985, President P.W. Botha offered Mandela release if he renounced armed struggle, which Mandela refused. Despite increasing local and international pressure, no agreement was reached until Botha suffered a stroke, and F.W. de Klerk succeeded him. Mandela was finally released on February 11, 1990. De Klerk lifted the ban on the ANC and removed restrictions on political groups, ending executions.

Nobel Peace Prize and Presidency

Following his release, Mandela urged foreign powers to maintain pressure on the South African government for constitutional reform. Committed to working for peace, he declared that the ANC’s armed struggle would continue until black citizens gained voting rights. In 1991, he was elected president of the ANC.

In 1993, Mandela and de Klerk jointly received the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to dismantle apartheid. This recognition followed negotiations between Mandela and de Klerk over South Africa’s first multiracial elections. Despite ongoing violence and resistance, Mandela successfully balanced political pressure with intensive negotiations.

On April 27, 1994, South Africa held its first democratic presidential elections. Mandela was inaugurated as the country’s first black president on May 10, 1994, at the age of 77, with de Klerk as his deputy. During his presidency from 1994 to June 1999, Mandela transitioned from minority rule and apartheid to majority rule. He used the nation’s enthusiasm for sports to foster reconciliation, encouraging black support for the previously unpopular national rugby team. In 1995, South Africa hosted the Rugby World Cup, enhancing the country’s global stature. Mandela also received the Order of Merit that year.

Throughout his presidency, Mandela protected South Africa’s economy from collapse through his Reconstruction and Development Program, creating jobs, housing, and basic healthcare. In 1996, he signed a new constitution into law, establishing a strong central government based on majority rule while guaranteeing minority rights and freedom of expression.

Retirement and Later Life

By the 1999 general elections, Mandela retired from active politics but remained busy. He raised funds to build schools and clinics in rural South Africa through his foundation, mediated the Burundian civil war, and was treated for prostate cancer in 2001. In June 2004, at the age of 85, Mandela officially retired from public life and returned to his childhood village of Qunu.

Death

In his final years, Mandela’s health declined. He suffered a lung infection in January 2011 and underwent surgery for a stomach illness in early 2012. After brief hospital stays in December 2012, March 2013, and June 2013, his wife, Graça Machel, canceled a planned trip to London to be with him. His daughter, Zindzi Dlamini, returned from Argentina to be by his side. Mandela passed away on December 5, 2013, at the age of 95, in his home in Johannesburg due to a lung infection.

Legacy

Mandela was married three times and had six children. He first married Evelyn Ntoko Mase in 1944, with whom he had four children: Madiba Thembekile, Makgatho, Makaziwe, and Maki. They divorced in 1957. The following year, he married Winnie Madikizela, with whom he had two daughters: Zenani and Zindzi. They separated in 1992 .

In 1998, Mandela married Graça Machel, the widow of former Mozambican president Samora Machel.

Mandela’s legacy endures through his commitment to justice, equality, and human dignity. His life symbolizes the power of perseverance and the importance of reconciliation and forgiveness in overcoming systemic injustice.