On June 19, 1991, 32 years ago, the head of the Medellín Cartel surrendered to the authorities. The role of a priest. The conditions of his VIP captivity. The lies to his wife while bringing in women. The incredible escape. And his inevitable end.

Father Rafael García Herreros, dressed in a white cassock and speaking calmly, used his program “El minuto de Dios” to have a two-hour meeting with the Devil.

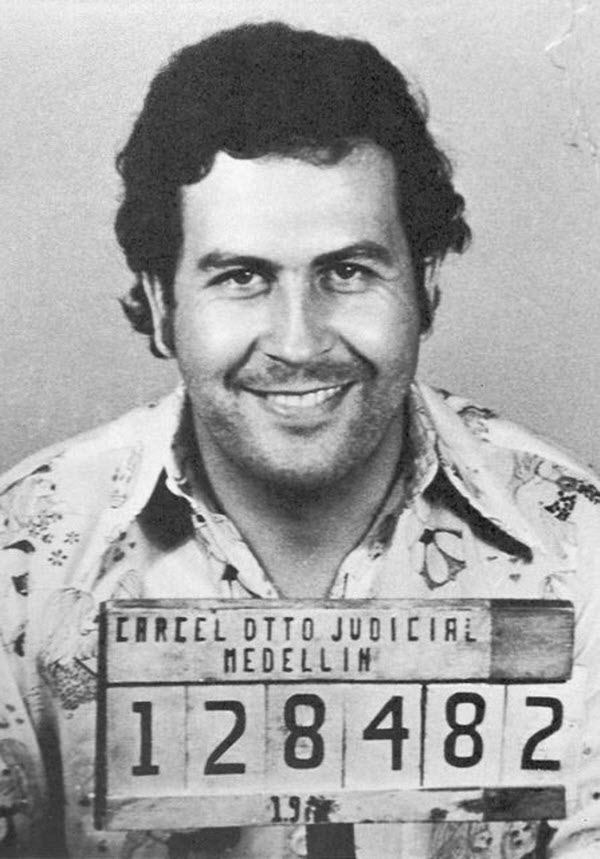

The Devil was a man who seemed invincible but was on the decline: the infamous drug lord Pablo Escobar Gaviria, “El Patrón del Mal.” On June 19, 1991, 32 years ago, he surrendered to the authorities for the crimes and attacks he had committed. The task was not easy. There were conditions: the first was that the intermediary had to be a priest.

The secret was revealed by the prestigious magazine Semana.

Two months earlier, when Escobar was holding his last two hostages and the state was offering a reward of 2.7 billion pesos for his capture, an emissary whose identity was never revealed sought out Father Rafael García Herreros, famous for his television program, and confessed that the only possibility for the surrender of the head of the Medellín Cartel was with his mediation.

Herreros was very discreet. He met with this mysterious man at a farm in Bogotá, where someone asked him to perform the necessary miracle for Escobar to surrender, which seemed impossible.

On the night of Thursday, April 4, the father recited the famous prayer to the sea of Coveñas.

“You who keep secrets, I would like to speak with Pablo Escobar, on the shore of the sea, right here, both of us sitting on this beach. They tell me he wants to surrender. They tell me he wants to talk to me. Oh, sea! Oh, sea of Coveñas at five in the afternoon when the sun is setting. What should I do? They say he is tired of his life and his struggles, and I can’t tell anyone, my secret. However, it is drowning me inside.”

Escobar, attentive to the TV programs, heard García Herreros’ message before he entrusted the matter to God: “The day that has passed and the night that is coming.”

“The envoy of God” did not wait for a response from the criminal. He traveled to Medellín to meet with the patriarch of the plan, Fabio Ochoa. Don Fabio took the priest to the Itagüí prison to introduce him to his sons.

“I want to talk to Pablo,” he said. And he wrote a message to Escobar, who replied with a four-page handwritten letter. There, he expressed his trust in the priest but demanded several conditions from the government for his surrender. One of them was that the members of the Elite Corps who had killed his cousin Gustavo Gaviria be sanctioned for violating human rights.

President César Gaviria and the Security Advisor, Rafael Pardo, did not respond to the requests.

After receiving a message, the priest was summoned to Fabio Ochoa’s estate, where he waited for Escobar’s call. “I was so scared that I hoped he wouldn’t answer,” the priest confessed at that time to Semana.

“Escobar reiterated his desire to surrender but told him that he feared being killed in prison, so he refused to be imprisoned in Itagüí, where his associates, the Ochoas, were held. The drug lord revealed that the hostages were well and would soon be released. He also clarified that he had not ordered the murders of the leftist candidates Jaime Pardo Leal, Bernardo Jaramillo, and Carlos Pizarro. The conversation lasted 45 minutes. At the end, García Herreros gave a blessing to Escobar and his entourage, who received it kneeling and holding scapulars. The parable of the shepherd and the black sheep divided the country,” Semana revealed.

“I prefer a grave in Colombia to a cell in the United States,” Escobar often said, as his greatest fear was being extradited to that country.

García Herreros was praised and criticized at the same time. Some called him the reincarnation of the devil for having contact with the worst criminal in Colombia’s history, while others nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize.

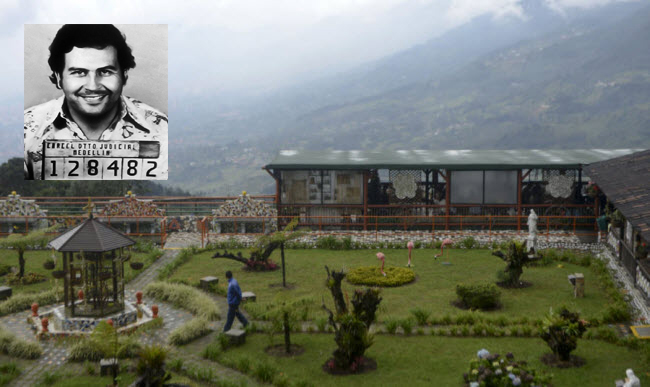

The surrender had been negotiated since November 1990. Escobar achieved what seemed utopian: the construction of a prison just for him. The mayor of Envigado, Jota Mario Rodríguez, offered his collaboration for the success of the extraditables’ surrender. He made available to the government a three-hectare plot of land in the village of La Catedral, where a rehabilitation center for drug addicts was being built, known as Claret. The then-Vice Minister of Justice, Francisco Albeiro Zapata, visited the construction site and gave it the green light.

In May, more than 60 workers worked on the over 1,800 square meters. The contract had a rather peculiar clause: “No police or military authority shall have access to the internal part of the prison establishment.”

Escobar was behind the construction of La Catedral. Located on the steepest part of a hill, the prison was shielded at its rear by a dense pine forest, making it inhospitable and impenetrable.

It was accessed by a steep and narrow 14-kilometer road from the urban center of Envigado, a 40-minute drive. The first checkpoint was a fenced guardhouse, guarded by the Military Police. The fence was electrified with 4,000 volts, and anyone who touched it would be electrocuted.

There was also a ring of ferocious bomb-sniffing dogs, a perimeter guarded by soldiers. The building had a steel roof to prevent bombings. Everything was in place for the surrender to occur on May 18, 1991, but two events prevented it: the origin of the appointed director of La Catedral, Jorge Pataquiva, who was from Girardot, and his guards, all from Cundinamarca. The head of the Medellín Cartel wanted all his guards to be from Antioquia. And second, the speech given by Father García Herreros on “El minuto de Dios” on May 7, where he reprimanded Escobar, calling him a “pornography reader.”

The drug lord was furious. “That was a mistake. The priest started by saying he wouldn’t talk about Escobar or the surrender and continued talking about God and the evils of pornography, but Escobar thought it was a scolding for him. That almost ruined the surrender. Later, Escobar learned from Father García himself that what was said at that time was not directed at him,” Father Jaramillo recalled to Semana.

There was another meeting where the matter was clarified.

On June 19 at noon, the National Constituent Assembly, after a vote of 51 to 13, decided to prohibit extradition.

Negotiator Alberto Villamizar and Father García Herreros went to Medellín to coordinate Escobar’s surrender. Escobar boarded the aircraft, shook hands with Villamizar and Father García Herreros, and minutes later landed inside La Catedral. There, he handed his weapon to Pataquiva, hugged his mother, Hermilda Gaviria, and his wife, Victoria Henao, whom he hadn’t seen in months.

After an hour-long conversation with journalist Alirio Calle, director of Teleantioquia’s news program, Escobar was behind bars. At 9 p.m., he read a statement that went around the world.

Luxury is not vulgarity

The room had a fireplace, large red, yellow, and blue candles with different scents, five paintings, a refrigerator full of food and champagne, and in the center, a large bed with a water mattress covered by high-quality blankets. At night, the attraction was the view of Medellín’s illuminated landscape through a large window.

This is not the description of a suite in a five-star hotel in Colombia. This was the place of detention for Pablo Escobar Gaviria, the head of the Medellín Cartel, in the La Catedral prison. Not just for his drug empire, but for the political assassinations he ordered.

His cell had no bars, no damp cement, no graffiti-covered walls, and certainly not the foul-smelling latrine found in every prison.

This place had been decorated by his wife, Victoria Eugenia Henao. She had given it a romantic touch, imagining passionate nights with the love of her life. The most famous drug lord in the world.

He was sent to “his” prison by helicopter, accompanied, among others, by the Eudist priest (from the Congregation of Jesus and Mary) Rafael García Herreros.

At the same time, his closest lieutenants also surrendered: Otoniel González (Otto), Carlos Aguilar (Mugre), John Jairo Velásquez (Popeye), Valentín de J. Taborda, Roberto Escobar (Osito), Gustavo González (Tavo), Jorge Eduardo Avendaño (Tato), and Johnny Rivera (El Palomo). The list continues: José Fernando Ospina (El Mago), John Jairo Betancur (Icopor), Carlos Díaz (La Garra), and Alfonso León Puerta (El Angelito).

More than a maximum-security prison, it seemed like a residence for mafiosos and hitmen.

“Finally, seven years after running and running, I was suddenly overwhelmed with a pleasant feeling of tranquility because I imagined that I would regain my femininity, my place as a wife, a mother, a companion, a lover. I thought he would serve many years in prison and that he would make amends with society,” Henao hoped.

But the criminal who would become a legend was not going to change his destiny of drug trafficking, murders, and war.

She would go up