During the filming of any movie, it’s common for the cast and crew to face some risks while shooting scenes. But what about a movie where its story and production were the danger itself? In this case, it wasn’t just one or two people who were injured, but more than 70 individuals, due to their interactions with numerous wild animals—some of which were not adequately trained. This happened in the movie Roar, which was released in 1981 and is considered one of the craziest films ever shot in Hollywood. The movie faced numerous problems behind the scenes, which delayed its production for a long period of five years. When it was finally completed, the crew breathed a sigh of relief as there were no fatalities, despite the many injuries, some of which were quite severe.

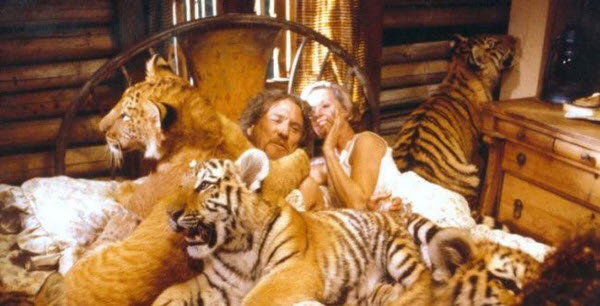

The plot of Roar revolves around “Hank,” a naturalist who lives in a wildlife reserve in Tanzania, Africa, with a group of lions, tigers, and leopards. His family, visiting from Chicago, arrives at his residence during his absence and faces various adventures amidst the wild animals in his home. Most of the film’s scenes focus on the actors fleeing, running, and hiding in fear as they are chased by groups of lions that scratch their faces and wrestle them to the ground.

While the story might seem conventional, what stands out is that the film’s director, lead actor, and writer, Noel Marshall, decided to make it a family project. He cast his wife, actress Tippi Hedren, his teenage stepdaughter Melanie Griffith, and his two sons, John and Jerry, in the film. Unfortunately, none of them emerged from the production unscathed. It was a shocking experience for Melanie Griffith, who left the project at one point, stating that she didn’t want to end up with half a face. She eventually returned to the set, only to be injured by a lion, requiring facial reconstructive surgery. The scene where Griffith is attacked can actually be seen in the final film. Tippi Hedren, on the other hand, suffered a severely injured leg after being crushed by the elephant “Tembo,” and a lion bit her on the back of the head. She also experienced broken bones when Tembo threw her to the ground during a riding scene, and she needed a skin graft to repair the damage from scratches and bruises, all of which are visible in the film.

Noel and John Marshall also suffered multiple injuries. One notable incident involved a lion biting John’s head and refusing to release it. It took six men and 25 minutes to free him from the lion’s grip, and he ended up with 56 stitches. However, this didn’t stop him from returning to the set just two days later. He later recalled the incident, saying it was incredibly painful, but he returned because he felt obligated. He also admitted that filming Roar gave him nightmares, acknowledging that while he had fun during the shoot, his father was quite harsh on them, refusing to stop filming even when the actors screamed for help. As for Noel Marshall, he endured numerous injuries, some captured on camera and others not, to the point where he developed gangrene and spent six months in the hospital recovering. In addition to his leg injuries from being dragged by a lion, it took him years to fully heal. The crew members didn’t escape harm either. Dutch cinematographer Jan de Bont had his scalp torn open by a lion, requiring 120 stitches to reattach his skin. Despite the obvious risks of filming wild animals up close, he returned to complete the project.

Due to the difficulty of shooting some scenes with the animals, which required weeks of training, and the numerous injuries during production, the film’s completion was delayed by nearly five years. It was originally scheduled to take six months, but filming began in October 1976, and the movie wasn’t released until 1981, and even then, it was outside the United States. The film wasn’t allowed to be shown in the U.S. until 2015, nearly 30 years later. The final version was released with a disclaimer stating, “No animals were harmed during the making of this film, but 70 cast and crew members were injured.”

The idea for Roar started to take shape after Noel Marshall and his wife, Tippi Hedren, took a trip to Africa, visiting the jungles of Zimbabwe and a wildlife reserve in Mozambique. There, they saw an old building inhabited by several lions, which inspired their cinematic vision of a scientist living in harmony with these lions and protecting them from poachers. Despite the simple premise, bringing it to life was far from easy. Initially, they planned to shoot the movie in Africa, but for production reasons, they ended up filming in California. They also intended to use trained wild animals with professional handlers, but they struggled to find the 30 or 40 lions required by the original script. This frustration led to the suggestion that they should raise and train the lions themselves. So, in 1971, they began raising lion cubs in their home in Sherman Oaks, a residential area where they lived with their three children. Marshall and Hedren believed that living with the lions would reduce the risk of the crew being attacked once filming began. Marshall later recounted sharing his home with the lions, saying:

“I lived in the house with them for about six months. We had a group of around 15 lions, which we called ‘the teenagers,’ and by 3 a.m., when you’re trying to sleep, they could kill you. But when they didn’t, you gained trust.”

Due to complaints from neighbors about the presence of wild animals, Noel Marshall and his wife were forced to relocate the lions to a farm outside Los Angeles. This farm became home to not only lions but also tigers, leopards, and even elephants. The location served as both a mini zoo and the filming site, but the production faced multiple disasters, including wildfires in the surrounding forests, floods that destroyed many filmed scenes, damaged equipment, and the deaths or escape of several lions. Local law enforcement had to shoot three of the escaped lions for public safety. These setbacks delayed the production for years and cost millions of dollars. The initial budget of $3 million ballooned to $17 million, with Marshall and Hedren personally funding a large portion after investors pulled out. When the film was finally released abroad, it grossed only $2 million. As if the series of misfortunes weren’t enough, the couple divorced a year after the film’s release, with some speculating that Roar played a part in their separation due to Marshall’s decision to expose Melanie Griffith to real dangers during filming, something her mother deeply resented.

The production of the movie was absolute madness. The chaotic atmosphere created immense fear during filming, leading one film critic to describe the crew as resembling hostages forced to play roles at gunpoint. Although Roar ostensibly promoted peaceful coexistence between humans and wild animals, the message seemed contradictory throughout the film, as the lions destroyed everything around them, devoured everything in sight, and terrified everyone they encountered.