The Falklands War was a short, undeclared conflict that lasted ten weeks between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1982, triggered by a dispute over two British territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands and its dependencies, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. The conflict began when Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands on April 2, followed by the invasion of South Georgia the next day. Three days later, the British government dispatched a naval task force to engage the Argentine Navy and Air Force before launching an amphibious attack on the islands. The conflict lasted 74 days and ended with Argentina’s surrender and the return of the islands to British control. During the conflict, 649 Argentine military personnel, 255 British military personnel, and three Falkland Islanders were killed. Diplomatic relations between the two countries were restored after a meeting in Madrid, Spain, in 1989.

Outbreak of the Falklands War

The Falklands War began when Argentina claimed sovereignty over the Falkland Islands, located 480 km east of its coast, since the early 19th century. However, Britain had occupied the islands since 1833, expelling the few remaining Argentinians and steadfastly rejecting Argentina’s claims of ownership. In early 1982, after the Argentine military junta led by General Leopoldo Galtieri came to power, negotiations with Britain were abandoned. Instead, Argentine troops launched an invasion of the islands, a decision driven politically by criticisms of the junta’s economic mismanagement and human rights abuses. The junta believed that reclaiming the islands would unite Argentinians behind the government and boost their patriotism. Elite forces trained in secrecy and were rapidly prepared for the operation, especially after a dispute on South Georgia, where Argentine workers raised the Argentine flag, prompting a swift naval buildup.

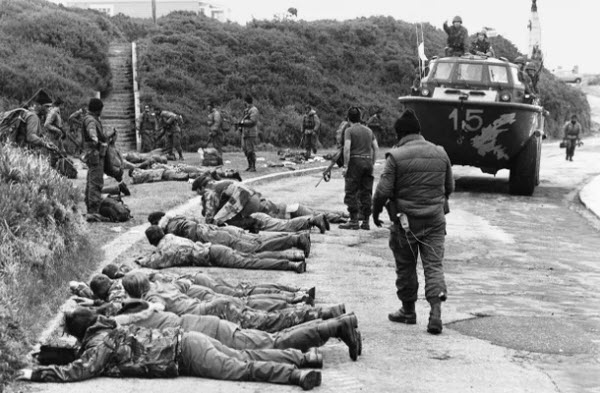

The Falklands War officially began when Argentine forces invaded the Falkland Islands on April 2, quickly overcoming the small British Marine garrison stationed in the capital, Stanley. Strict orders from the Argentine command forbade inflicting casualties on the British, despite losses to their own units. The following day, Argentine Marines seized South Georgia. By late April, Argentina had deployed over 10,000 troops to the Falklands, though most were poorly trained conscripts lacking adequate food, clothing, and shelter as winter approached.

As anticipated, the Argentine public reacted positively, with large crowds gathering in Plaza de Mayo (in front of the presidential palace) to show support for the military initiative. In response to the invasion, the British government, led by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, declared a 320 km exclusion zone around the Falklands as a war zone and assembled a naval task force to proceed to the area. Most European powers expressed support for the United Kingdom, and European military advisors were withdrawn from Argentine bases. Most Latin American governments sympathized with Argentina, with Chile being a notable exception due to its military readiness against Argentina over a dispute in the Beagle Channel. This perceived threat from Chile led Argentina to keep most elite forces on the mainland, away from the Falklands. Argentine military planners were confident that the United States would remain neutral, but this confidence waned as attempts at mediation failed, leading to full U.S. support for Britain. This support allowed Britain’s NATO ally to use its air-to-air missiles, communications equipment, aircraft fuel, and other military supplies from Ascension Island, as well as to cooperate with military intelligence.

Course of the Conflict

On April 25, while the British task force sailed 13,000 km to the war zone via Ascension Island, a small British force recaptured South Georgia and seized an old Argentine submarine. On May 2, a British nuclear submarine sank the old Argentine cruiser General Belgrano (purchased from the U.S. after World War II) outside the exclusion zone. Following this controversial event, most other Argentine ships remained in port to preserve them, with the Argentine Navy’s contribution limited to its naval air force and one of its newest German-made diesel-electric submarines, which posed a greater threat to the British fleet than anticipated. The submarine launched torpedo attacks but failed narrowly. For the British, the challenge was their reliance on only two aircraft carriers, as losing one would almost certainly force them to withdraw. The air cover was limited to about 20 short-range Sea Harrier aircraft armed with air-to-air missiles, compensating for the lack of long-range air cover. Destroyers and frigates were positioned ahead of the fleet to serve as radar pickets, but not all were equipped with full anti-aircraft systems or close-in weapons to shoot down incoming missiles, leaving British ships vulnerable. On May 4, the Argentinians sank the destroyer Sheffield with an Exocet missile, while Argentina lost about 20-30% of its aircraft.

Due to these losses, the Argentinians could not prevent the British from landing on the islands. The Argentine ground commander on the islands, General Mario Menéndez, anticipated a direct British assault and concentrated his forces around the capital, Stanley, to protect its vital airfield. Instead, British Admiral John Woodward and Major General Jeremy Moore decided to make their initial landing near San Carlos on the northeastern coast of East Falkland and then launch a land assault on Stanley. This strategy aimed to avoid casualties among British civilians and troops. The British landed unopposed on May 21, but the approximately 5,000 Argentine defenders quickly organized effective resistance, leading to intense clashes. Meanwhile, Argentine air forces continued to attack the British fleet, sinking two frigates, a destroyer, a helicopter transport ship, and a troop transport, and damaging several other frigates and destroyers. However, they failed to destroy the aircraft carriers or sink enough ships to jeopardize British land operations and lost a significant portion of their remaining jet aircraft, helicopters in the Falklands, and light ground-attack aircraft.

From the San Carlos bridgehead, British infantry advanced rapidly southward through harsh weather conditions to capture the settlements of Darwin and Goose Green. After several days of fierce fighting against Argentine troops stationed along various ridge lines, the British succeeded in capturing and occupying the high ground west of Stanley. With British forces surrounding the capital and main port, it became evident that the large Argentine garrison was isolated and could be starved out. Consequently, Menéndez surrendered on June 14, effectively ending the conflict. British forces also removed a small Argentine garrison from one of the South Sandwich Islands, about 800 km southeast of South Georgia, on June 20.

Costs and Consequences of the Falklands War

The British captured about 11,400 Argentine prisoners during the Falklands War, all of whom were released afterward. Argentina reported about 649 deaths, half of which were from the sinking of the cruiser Belgrano, while Britain lost 255 personnel. Military strategists discussed the key aspects of the conflict, generally highlighting the roles of submarines (British nuclear and old Argentine diesel-electric submarines) and anti-ship missiles (both air-to-sea and sea-to-sea). The Falklands War demonstrated the importance of air superiority, which the British struggled to establish, and advanced surveillance. Logistical support was also crucial, as both countries’ armed forces operated at their maximum ranges.

The loss of the Falklands War severely damaged the credibility of the Argentine military government due to its failure to prepare and support its forces for the invasion it ordered. Civilian rule was restored in Argentina in 1983. Meanwhile, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher turned widespread national support into a decisive victory for her Conservative Party in the 1983 general election. In 1989, diplomatic relations between the United Kingdom and Argentina were restored after a meeting in Madrid, where the two governments issued a joint statement that did not clarify any changes in either country’s position on the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands. In 1994, Argentina adopted a new constitution declaring the Falkland Islands as part of one of its provinces. Nevertheless, the islands continue to operate as a British Overseas Territory with self-governance.