In many romantic novels, we read that when one lover dies, the other lives on in their memory forever, and sometimes may even take extreme measures to join them in the afterlife. Though this notion might seem fantastical, India—a country often seen as a land of wonders—has taken such matters seriously through the practice of Sati. This bizarre tradition involves a widow self-immolating on her deceased husband’s funeral pyre, under the belief that they will continue their lives together in the afterlife. Despite the insanity of this idea, many locals view it as a heroic and courageous act, a profound testament to a wife’s devotion to her husband. Over the years, this tradition has resulted in the deaths of thousands of women across the country, prompting authorities to criminalize and impose severe penalties on its perpetrators.

The term “Sati” in Indian texts and Sanskrit means “the pure and chaste woman” and is linked to the goddess Sati, the wife of the deity Shiva. According to Hindu mythology, Sati’s father, the deity Daksha, despised Shiva, and in protest, Sati self-immolated while praying to be reborn as Shiva’s wife. This legendary tale is often cited as a justification for the practice, viewed as a demonstration of love and unity between spouses. However, this justification is flawed, as the Sati in the myth was not a widow and was, according to their beliefs, a goddess with supernatural abilities, unlike ordinary humans.

Historically, Sati was initially practiced as a voluntary act, demonstrating a wife’s loyalty by following her husband into the afterlife. Over time, it evolved into a compulsory tradition due to societal beliefs that widows were burdens to the community, especially if they had no children. Women were pressured to perform Sati under the belief that such a woman would die pure and thus have a better rebirth, given their belief in reincarnation. Sati was not practiced if the widow was pregnant or had young children.

Historical records suggest that Sati began before the Common Era, with documented evidence from the Gupta Empire period. It spread from India to Nepal and later to Rajasthan. Initially limited to royal families, a memorial stone called the “Sati Stone” was erected for queens who died in this manner. Before their deaths, queens would often leave handprints on the wall to be remembered as brave and devoted wives. This monument remains within the Mehrangarh Fort. Over time, the practice spread to lower social classes and peaked between the 15th and 18th centuries. Estimates indicate that around 1,000 women were burned alive annually. The horror of this tradition led to its prohibition at various times, beginning with Mughal Emperor Akbar in 1582, followed by Portuguese, French, and British colonialists, who enacted stringent laws against it in 1850. British Governor Sir Charles Napier ordered the execution of any Hindu priest presiding over such ceremonies.

In modern times, despite increased awareness, this abhorrent practice has not entirely disappeared. In 1987, in the village of Dourala, Rajasthan, an 18-year-old woman named Roop Kanwar was forced into Sati when her husband died eight months after their marriage. Despite her resistance, villagers drugged and burned her alive. Following an investigation, those responsible were arrested, and the government enacted legislation criminalizing the practice, with penalties including death for anyone forcing or encouraging a woman to commit Sati. However, despite these protective laws, some widows still choose to practice Sati, with at least four cases recorded between 2000 and 2015.

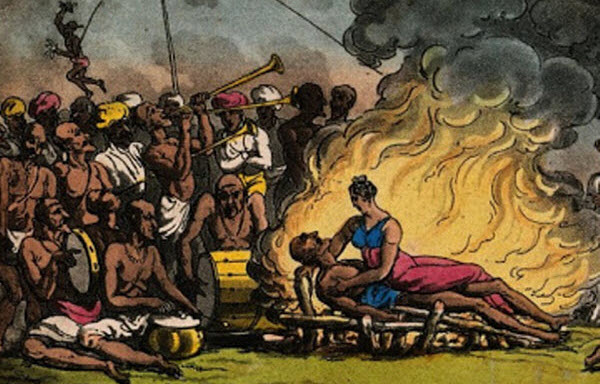

The methods of performing Sati vary. Sometimes, the woman sits on her husband’s funeral pyre or lies beside his corpse. In other cases, a small hut is built where the woman and her husband are burned together, or the husband is placed in a pit of flames, and the wife jumps in while still burning. Occasionally, the wife may be allowed to consume poison or drugs or be exposed to venomous snakes to ensure she is not fully conscious during the burning.