A year after World War II ended, nations and their citizens were slowly returning to their normal lives, trying to forget the horrors and destruction the war had brought. Among those trying to move on were tens of thousands of English football fans who decided to enjoy a football match in the FA Cup, the first major football tournament organized in England after the war. The match was between Bolton Wanderers and Stoke City, but what was supposed to be a joyful event turned into a tragic catastrophe. Dozens of Bolton fans were killed, and hundreds were injured in what became known as the Burnden Park Disaster. Strangely, the match continued as planned, even with the bodies of the victims lying on the touchlines.

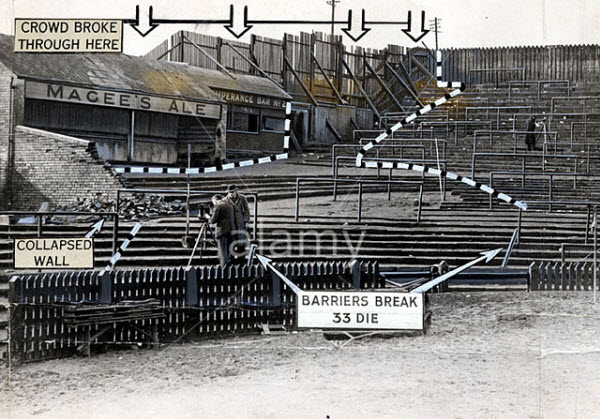

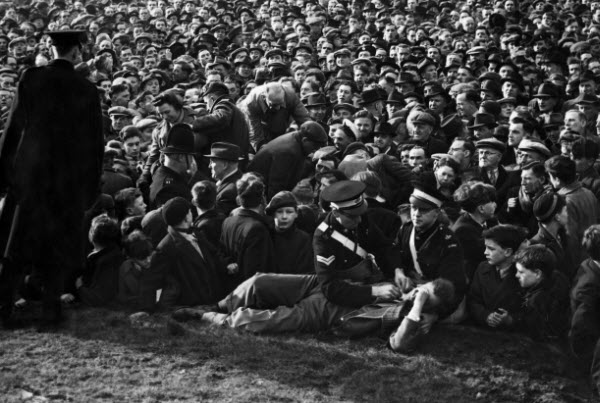

On March 9, 1946, Bolton Wanderers and Stoke City met for their FA Cup quarter-final match at Burnden Park in the United Kingdom. The British authorities expected around 55,000 spectators to attend the match at Burnden Park, which had a capacity of 70,000. However, those estimates turned out to be incorrect as a total of 85,000 people attended the match. Some of them somehow managed to enter the stadium without tickets, and once the stands were full, the turnstiles were closed at 2:40 pm. It quickly became clear that there were far too many people in the stadium. Additionally, many fans who couldn’t get in began climbing over the turnstiles, increasing the pressure on the already overcrowded stadium. This led to a deadly crush as fans surged forward onto the pitch, causing several barriers to collapse and people to be trampled underfoot. The tragic incident resulted in 33 deaths and hundreds of injuries in what the media later called the “Burnden Park Disaster.”

All of this chaos unfolded while the match was already underway. The game was stopped twice; the first time when some fans rushed onto the pitch, but it resumed after they were cleared away. The second stoppage occurred in the 12th minute when the barriers collapsed, causing the deadly crush among the spectators. The authorities quickly moved to contain the disaster. A police officer approached the match referee, George Dutton, and informed him of the fatalities. Dutton then called over the team captains, Harry Hubbick of Bolton and Neil Franklin of Stoke, and they unanimously agreed to suspend the match. The players began to leave the pitch as the British authorities worked to rescue the injured and remove the bodies of the deceased, placing them along the touchlines covered with coats. Some reports suggest that new touchlines were marked with sawdust to separate the bodies from the players, who returned to the field to resume the match after a 30-minute delay. Legendary player Stanley Matthews, who was a member of the Stoke team that day, later stated that he felt sick to his stomach at the decision to continue the game.

The disaster was a major tragedy at the time, leading to the formation of an investigative committee that issued a formal report known as the “Moelwyn Hughes Report.” The report included a set of recommendations for stricter monitoring of crowd sizes during matches, ensuring that football grounds are properly organized, and equipping them with internal telephones for easy communication. It also recommended that turnstiles mechanically record the number of spectators. In response, the Football Association organized a charity match in August of the same year between England and Scotland, with the proceeds going to the victims of the disaster.

Despite the criticism over continuing the match amid such a tragedy and with bodies lying along the touchlines, some argue that the British public was somewhat desensitized to such scenes after experiencing similar sights in the streets during the war. Thus, they weren’t as affected by what they saw at the stadium. Although the disaster was horrific, it is less well-known than other similar incidents. Some players who later played for Bolton Wanderers said they were unaware of the disaster when they joined the club. Years later, in 1992, a memorial plaque bearing the names of the victims was unveiled at the stadium. When the club moved to a new ground in 2000, the plaque was transferred to the new location to ensure it remained in a fitting place of honor.