Over the decades, numerous scientists have conducted experiments that advanced human knowledge and propelled progress. However, some researchers ventured into unusual and bizarre experiments, driven by the quest to answer seemingly impossible questions. One such experiment took place in the early 20th century, conducted by Dr. Duncan MacDougall, a physician from the United States. MacDougall was intrigued by the notion of the human soul and sought to determine whether it possessed physical mass or could be measured. This curiosity led him to undertake a series of controversial experiments that sparked considerable debate among the medical community.

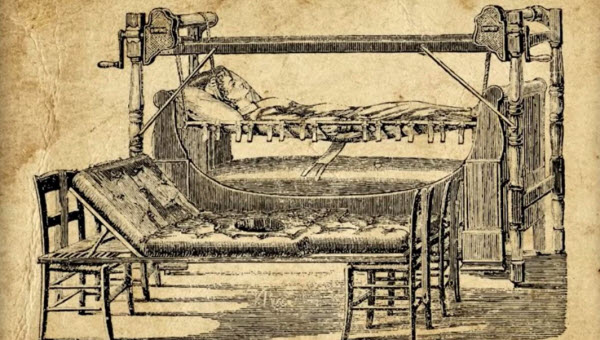

In 1901, Dr. Duncan MacDougall, based in Massachusetts, embarked on a series of unconventional experiments fueled by his fascination with the idea that the human soul had physical weight. To conduct his research, he prepared a bed equipped with sensitive scales and selected a group of terminally ill patients. He convinced these patients to lie on the bed during their final moments, meticulously recording not only the time of death but also any changes in their weight before and after passing away. He accounted for bodily fluids such as sweat and urine, as well as gases like oxygen and nitrogen, and began documenting his observations.

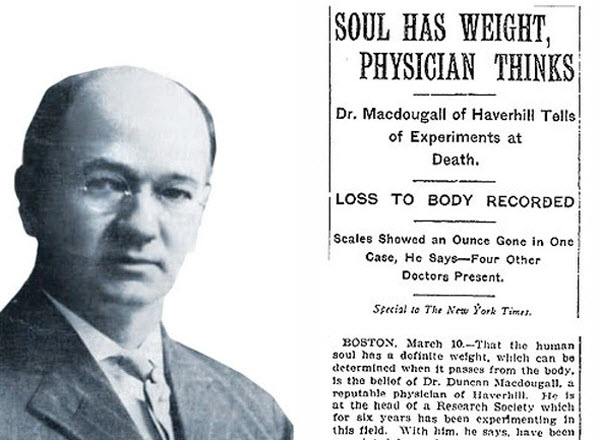

MacDougall’s findings led him to conclude that the human soul weighed 21 grams. Despite this assertion, some experiments showed that one patient lost weight and then regained it, while two others experienced weight loss that increased over time. Only one patient demonstrated an immediate weight loss of 21.3 grams coinciding with the time of death, while results from two other patients were dismissed due to potential inaccuracies in the scales.

MacDougall did not limit his experiments to humans alone; he also tested fifteen dogs, none of which showed significant weight loss. This result supported his belief, aligned with his religious convictions, that animals lacked souls. However, it remains puzzling how MacDougall could have obtained fifteen dying dogs in such a short period, leading to speculation that he might have poisoned healthy animals for his research.

Although these experiments might seem peculiar and unlikely to receive serious attention from today’s scientific community, the thought processes and reactions they provoked continue to resonate. After completing his experiments, MacDougall’s findings were published in journals such as the “Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research,” “American Medicine,” and the “New York Times” in March 1907. The articles sparked a heated debate, particularly with Dr. Augustus P. Clark, who suggested that the weight loss observed was due to the cessation of blood cooling by the lungs at the time of death, leading to a slight rise in body temperature and sweating.

MacDougall responded in subsequent publications, arguing that the circulatory system ceased functioning at death, which should not cause skin temperature increases. The debate continued through late 1907, but the medical community largely dismissed MacDougall’s experiments, with only a few supporters remaining.

Four years later, MacDougall made headlines again in 1911, announcing that he would not only weigh the human soul but also attempt to capture it on X-ray at the moment of departure from the body. Despite his concerns that the spiritual essence might be disturbed by X-ray imaging, he conducted dozens of experiments, capturing what he described as ethereal light in the skulls of deceased patients.

Years passed, and MacDougall died in 1920, leaving behind a small group of devoted followers and a larger group of skeptical medical professionals. Despite the criticism, his experiments remain intriguing, as they opened avenues for exploring the mysteries of existence. Today, we still struggle to fully understand how our brains perform their functions and continue to search for dark matter, which makes up over 80% of the universe’s mass, despite never having observed a single particle. Some even speculate that the soul might be a result of electromagnetic waves generated by our brains, although this idea is largely rejected by scientists.