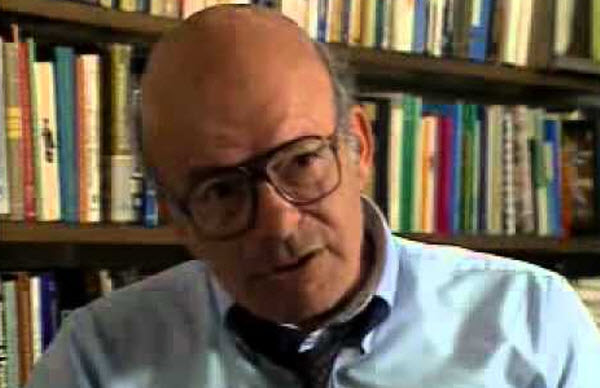

Errors are part of the human condition, but in some professions, such mistakes can be catastrophic, especially in engineering or medical fields where they can threaten human lives. In medicine, diagnostic errors can lead to incorrect treatments with potentially dire consequences. This concern led one doctor in the late 1960s to conduct a unique and controversial study known as the Rosenhan Experiment. The aim was to demonstrate that sometimes it is challenging for doctors to distinguish between the sane and the insane in psychiatric hospitals. To test this, he, along with seven mentally healthy individuals, posed as psychiatric patients and stayed in psychiatric hospitals from 1969 to 1972. They acted as patients to see if the doctors could discern their pretense of insanity. The results were startling.

The story of the Rosenhan Experiment began in the United States in 1969 when eight sane individuals entered twelve different psychiatric hospitals across five states, except one federally operated facility. The team consisted of three women and five men, including Professor Rosenhan himself, who was a psychiatrist and artist. The participants used fake names and professions and were instructed to schedule appointments with hospitals and claim they were hearing strange voices. Based on these symptoms, each was admitted to the hospital they contacted. The team was surprised at how easily they were admitted. They were all diagnosed with schizophrenia, except one, who was diagnosed with manic-depressive psychosis, despite all they did was feign auditory hallucinations and did not exhibit any other symptoms or fabricate details about their lives, except for their names and professions. Nevertheless, they were diagnosed with severe mental disorders.

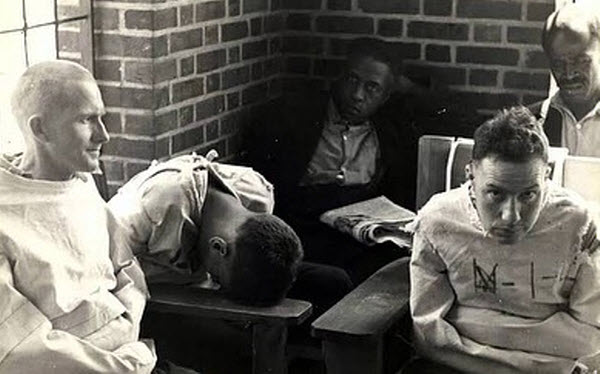

Once admitted, the team members were on their own, with no indication of when the doctors would recognize their deception or when they would be discharged. Initially, the greatest concern was being discovered quickly, but as it turned out, this fear was unfounded. Rosenhan noted a unified failure in diagnosis; the hospital staff never suspected that they were faking their illness. Even when the fake patients reported that their hallucinations had ceased, the doctors and staff continued to believe their diagnoses were correct. For example, Rosenhan instructed the fake patients to take notes about their experiences. One supervising nurse noted in her daily report, “The patient is engaging in writing about his behavior.”

This revealed a troubling aspect of the Rosenhan Experiment: doctors and staff appeared to believe their initial, incorrect diagnoses were accurate, and they adapted their observations to fit this belief. Rosenhan commented on a nurse’s report:

“Given that a patient in the hospital should be mentally disturbed, and because they are disturbed, continuous writing should be a behavioral manifestation of that disorder and perhaps a subset of compulsive behaviors sometimes associated with schizophrenia.”

One example of the errors in psychiatric diagnosis revealed by the experiment was a fake patient who described his home life as unstable with his wife and children. However, because he was admitted to a psychiatric hospital and diagnosed with schizophrenia, his discharge report stated that he had recovered from this illness without considering his family circumstances and that he might have improved upon distancing himself from these pressures.

In addition to the stubbornness of doctors in maintaining their diagnoses, the hospital staff treated the fake patients with indifference or even harshness. The interactions with staff ranged from a lack of concern to outright cruelty. Even when the fake patients tried to engage staff in friendly conversation, the responses were routine. Surprisingly, while the staff treated the fake patients poorly without ever realizing they were impostors, real patients were aware of the truth, with some even telling the impostors directly, “You’re not insane… you’re a journalist or researcher.” Nevertheless, the doctors were never wise to this. The fake patients were eventually released, with hospital stays ranging from 7 to 52 days, with an average of 19 days. All were discharged with the same diagnosis they received upon admission, though they were released because the doctors deemed their conditions relatively stable.

Rosenhan made a note upon their release:

“At no time during any hospitalization was any question raised about the pretense of any of the patients, and there is no evidence in the hospital records during the Rosenhan experiment to suggest that the false patient’s condition was ever doubted. Instead, there is strong evidence that the false patient, described as having schizophrenia, was stuck with that label. If the false patient was to be released, it was because of their calmness, not because they were deemed sane by the institution.”

Rosenhan concluded in his report that it was clear that psychiatric hospitals could not reliably distinguish between the sane and the insane and theorized that the hospitals’ desire to admit sane individuals resulted from what is known as a “Type 2” or “false positive error,” which results in a greater inclination to diagnose a healthy person as sick rather than a sick person as healthy. This mindset is somewhat understandable, but failing to diagnose a sick person has more severe consequences than diagnosing a healthy person incorrectly. Nonetheless, the latter can also have grave repercussions.

The publication of the Rosenhan Experiment caused a stir, shocking people with the unreliability of psychiatric diagnoses and the ease with which hospital staff were deceived. However, some researchers criticized the experiment, noting that the dishonest reporting of symptoms by the fake patients rendered the study flawed, as patients’ self-reports are a fundamental part of psychiatric diagnoses. Other researchers supported Rosenhan’s conclusions and results, with some even replicating parts of his experiment and reaching similar conclusions.

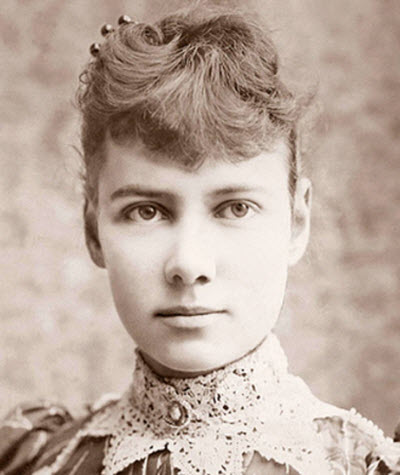

The Rosenhan Experiment was not the first to highlight the dark side of the mental health system in the United States. In 1887, journalist Nellie Bly went undercover in a psychiatric hospital and published her findings under the title “Ten Days in a Mad-House,” concluding that many other patients were “sane” like herself and had been unjustly committed. Bly’s work led to an investigation and the formation of a commission that attempted to conduct more thorough psychiatric examinations to ensure that those committed were indeed mentally ill. Nearly a century later, Rosenhan did the same and showed that the mental health profession still had a long way to go in reliably and consistently distinguishing between the sane and the insane.

Following the publication of the Rosenhan Experiment, the American Psychiatric Association revised the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The new edition, published in 1980, included a more comprehensive list of symptoms for each mental illness, stating that multiple symptoms should be present for a diagnosis rather than just one. These changes to the manual have continued to this day, although it is still not definitively known whether they have successfully prevented diagnostic errors.

Since the fake patients in the Rosenhan Experiment will never be able to speak about their participation, and since relatively little has been formally written about the study itself, the experiment has become difficult to discuss and critique due to the lack of controversy surrounding it. Nevertheless, subsequent research using documents from the original experiment has found errors in Rosenhan’s study. Journalist Susanna Cahalan cited primary sources such as correspondence, diary entries, and excerpts from Rosenhan’s unfinished book, finding that such documents contradicted some of Rosenhan’s published results. For example, Rosenhan himself admitted while undercover in an institution that he told doctors his symptoms were severe, which explained why he was quickly diagnosed, contradicting Rosenhan’s report that he had only described relatively mild symptoms, making the doctors’ diagnosis appear exaggerated. Furthermore, Cahalan was able to trace one of the fake patients who summarized their experience inside the psychiatric facility as positive, contrary to Rosenhan’s report of terrifying moments for himself and his team, which he had deliberately omitted when writing his report.

Nevertheless, whether these claims are accurate or not, and whether the Rosenhan Experiment fully proved its foundational claims, it may have contributed, in one way or another, to a more careful monitoring of diagnoses to avoid repeating old problems.