Winston Churchill was a statesman, writer, orator, and inspiring leader who led Britain through one of the darkest periods in its history. He took control during the peak of World War II and guided his people to withstand the German onslaught that swept across Europe. His strategies, in collaboration with allies, ultimately contributed to the defeat of Nazi Germany. Churchill was also one of the first to foresee the onset of the Cold War and warned the West about the dangers of communism. He remains a prime example of the famous saying “the right man at the right time,” honored by the Queen and his fellow citizens, and topped the list of the greatest Britons in a BBC poll in 2002, surpassing other notable figures like Charles Darwin and William Shakespeare.

Early Life

Winston Spencer Churchill was born on November 30, 1874, at Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire, England. He was the son of Lord Randolph Churchill, who came from a prominent English family, and Jennie Jerome, an American from New York City. He grew up in Dublin, Ireland, where his father worked for his grandfather, the 7th Duke of Marlborough, John Spencer-Churchill. During his schooling, Churchill was known to be a rebellious student. After poor performance in his first two schools, he enrolled in Harrow School near London in April 1888. Within weeks, he joined the Harrow Rifle Corps, marking the beginning of his military career.

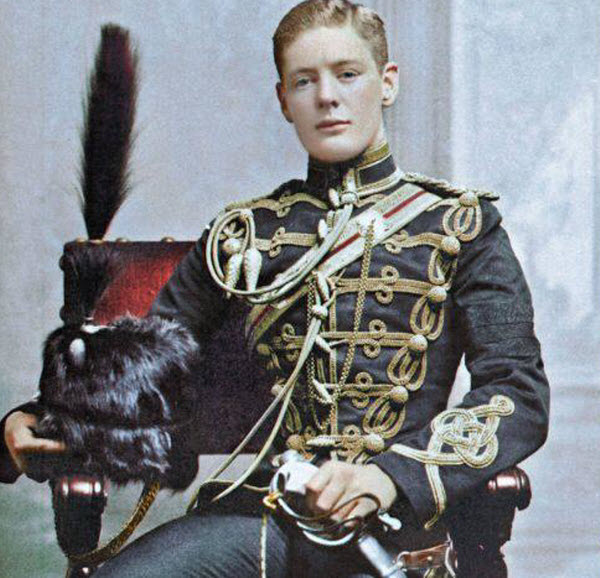

Initially, a military career didn’t seem like a good fit for Churchill, as it took him three attempts to pass the entrance exam for the Royal Military College. However, once he joined, he performed well, graduating 20th out of a class of 130. Despite his academic and professional success, his relationship with his parents was strained. He often wrote letters to his mother, pleading with her to visit him at school, but she seldom did. His father passed away when Churchill was 21, and it was said that Churchill barely knew him due to their distant relationship.

Military Career

Winston Churchill joined the British Army, and although his service was short, it was eventful. In 1895, he joined the 4th Queen’s Own Hussars and served in India and Sudan, participating in the Battle of Omdurman in 1898. During his time in the military, he regularly sent reports to prominent British newspapers such as the “Pioneer Mail” and the “Daily Telegraph.” He authored two books based on his experiences: “The Story of the Malakand Field Force” (1898) and “The River War” (1899). That same year, he left the army to work as a war correspondent for the “Morning Post,” a conservative daily newspaper. During the Boer War in South Africa, he was captured but managed to escape, making headlines in British newspapers and becoming a public hero. Churchill continued to travel, eventually making his way to Mozambique, and after returning to the UK in 1900, he wrote a new book, “London to Ladysmith via Pretoria,” detailing his recent experiences.

Political Career in Parliament and Cabinet

By 1900, Churchill became a Member of Parliament for the Conservative Party representing Oldham, a town in Manchester. He supported social reform, which was at odds with his party’s views, prompting him to switch to the Liberal Party in 1904. He was re-elected as an MP in 1908, the same year he married Clementine Ogilvy Hozier. They had five children: Diana, Randolph, Sarah, Marigold (who died young), and Mary. After his re-election, Churchill was appointed President of the Board of Trade, where he opposed the expansion of the Royal Navy, introduced prison system reforms, and established the first minimum wage. He also helped create labor exchanges and unemployment insurance.

Churchill also played a key role in passing the “People’s Budget,” which imposed taxes on the wealthy to fund new social welfare programs, enacted in 1910. Despite his humanitarian legislation, he showed a harsher side in 1911 when he made a controversial visit to a police siege in London involving two burglars hiding in a building. While accounts vary on his involvement, some suggest he merely went to see what was happening, while others claim he directed the police on how to storm the building. What is certain is that the building caught fire during the siege, and Churchill prevented firefighters from extinguishing the flames, stating it was better to let the building burn than risk lives. The bodies of the burglars were later found in the charred ruins.

First Lord of the Admiralty

In 1911, Winston Churchill was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty, a senior political position responsible for overseeing the British Navy. He modernized the fleet and ordered the construction of new oil-powered warships, replacing coal-fired engines. He was an early advocate for military aviation within the navy and established the Royal Naval Air Service. Enthusiastic about aviation, Churchill even took flying lessons to understand its military potential directly. In 1913, he drafted controversial legislation to amend the Mental Deficiency Act, advocating for the sterilization of the “feeble-minded,” a bill eventually passed by Parliament.

World War I

Churchill remained as First Lord of the Admiralty during the early stages of World War I but was forced to resign due to his role in the disastrous Gallipoli Campaign against the Ottoman Empire. He left the government in late 1915 and briefly rejoined the British Army, leading a battalion on the Western Front. In 1917, he was appointed Minister of Munitions in the final year of the war, overseeing the production of weapons, including tanks, aircraft, and ammunition.

After the war, from 1919 to 1922, Churchill served as Minister of War and Air and Secretary of State for the Colonies under Prime Minister David Lloyd George. As Colonial Secretary, he stirred controversy by ordering the use of air power against rebellious Kurdish tribes in Iraq, then a British colony. At one point, he proposed using chemical gas to suppress the rebellion, a suggestion considered but ultimately not implemented.

Due to numerous divisions within the British political landscape that led to Churchill losing his parliamentary seat in 1922, he left the Liberal Party and returned to the Conservatives. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer, returning Britain to the gold standard and taking a tough stance against the general strike of workers that threatened to paralyze the British economy. After the Conservative government was defeated in 1929, Churchill left government, viewed as an extreme right-wing figure out of touch with the public.

Hobbies in Painting and Writing

After being ousted from government in the 1920s, Churchill turned to painting, later writing, “Painting came to my rescue in the most trying times.” He painted over 500 canvases, often working outdoors, and claimed that painting greatly improved his memory and observational skills. During the 1930s, he focused on writing, publishing memoirs and biographies of the 1st Duke of Marlborough. He also worked on his famous book, “A History of the English-Speaking Peoples,” although it wasn’t published until two decades later. During this period, activists in India demanded independence from British rule, a movement Churchill opposed. He even insulted Gandhi, saying, “It is alarming and nauseating to see Mr. Gandhi, a seditious lawyer from Middle Temple, striding half-naked up the steps of the Vice-regal palace to parley on equal terms with the representative of the King-Emperor.”

World War II

Though Churchill initially did not perceive the threat posed by Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in the 1930s, he gradually became a staunch advocate for British rearmament. By 1938, as Germany began dominating its neighbors, Churchill became a fierce critic of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement policy toward the Nazis. On September 3, 1939, the day Britain declared war on Germany, Churchill was reappointed First Lord of the Admiralty and a member of the War Cabinet. In April 1940, he became chairman of the Military Coordinating Committee, the same month Germany invaded Norway. This invasion was a setback for Chamberlain, who had rejected Churchill’s suggestion that Britain should preempt the German invasion by occupying Norway’s iron ore mines and seaports.

On May 10, 1940, Chamberlain resigned, and King George VI appointed Churchill as Prime Minister and Minister of Defence. Within hours of his appointment, the German army launched its western offensive by invading Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg. Two days later, German forces entered France, leaving Britain to fight alone against the Germans. To confront this threat, Churchill quickly formed a coalition government comprising leaders from the Labour, Liberal, and Conservative parties, appointing smart and talented individuals to key positions. On June 18, 1940, he delivered one of his famous speeches to the House of Commons, warning that “the Battle of Britain” was about to begin. He devised clever policies to lay the foundation for an alliance with the United States and the Soviet Union. Churchill had previously established good relations with U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, and by March 1941, he had secured American aid allowing Britain to order war products from the U.S. on credit.

With the United States’ formal entry into World War II in December 1941, Churchill was confident that the Allies would eventually win. He worked closely with U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin to formulate an Allied war strategy and a post-war world order, meeting at the Tehran Conference in 1943, the Yalta Conference in 1945, and the Potsdam Conference later that year to develop a unified strategy against the Axis Powers and shape the post-war world through the United Nations.

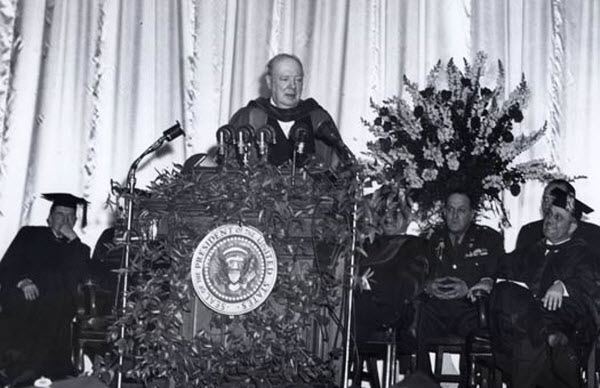

After the war, Churchill proposed plans for social reforms in Britain but failed to persuade the public that he could lead the country in peacetime, losing the general election in July 1945. While disappointed, Churchill spent the next six years leading the opposition party and continued to exert influence on world affairs, particularly in warning of Soviet expansion and the ensuing Cold War. In a famous speech in Fulton, Missouri, he declared that “an iron curtain has descended across Europe.” During this period, he authored a monumental work, the six-volume “History of the Second World War” (1948-1953), for which he won the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Later Years

Churchill returned to office in 1951. Over the next four years, he tried to combat the loss of the British Empire, strengthen Anglo-American relations, and help to create post-war Europe, ultimately becoming a central figure in the Cold War. He retired as Prime Minister in 1955 but remained an MP until 1964 when he retired from politics. He made his final public appearance in 1964 at the State Funeral of John F. Kennedy, the President of the United States. He lived another year, finally succumbing to a stroke on January 24, 1965, at the age of 90.

Churchill was given a state funeral attended by dignitaries from over 100 countries, including Queen Elizabeth II. His influence and legacy remain a significant part of modern British history.